Reeve Lindbergh spoke about her father, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, at the Coolidge Foundation on August 2nd, and she packed the Union Christian Church. Her father, “The Lone Eagle,” as he was popularly known, is the exception to Emerson’s rule that all heroes become bores. His name still retains its magic.

Charles Lindbergh was born on February 4, 1902, to a Swedish father, Charles A. Lindbergh, Sr., and a English-Irish mother, Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh. His father was a lawyer and Minnesota politician of radical persuasion. He served in the U.S. House of Representative from March 1907 to March 1917; thereafter, he ran unsuccessfully for senator and later governor. He died in 1924 while on the campaign trail. Lindbergh’s mother was a teacher of science. When the boy was seven years old, his parents separated, and thereafter he spent time with each.

Lindbergh was a daredevil with an innate interest in things mechanical, especially as concerned mechanized transportation. In his youth, he took to cars and motorcycle and eventually to flying machines. This was at time when airplanes fell from the sky to earth with regularity. But young Lindbergh was confident in himself and in his ability to handle risks and challenges. He was analytical in thought, a careful planner, and particularly good at judging and managing risk. Moreover, “Lucky Lindy,” as was known to millions, was one of those rare individuals, who, with Death in his many forms always at hand, lived a charmed life. Eventually, he would die an old man in his own bed. Another famous and daring pilot, Bert Acosta, said this of Lindbergh, “…he is above all things a lucky flier.”

On May 20, 1927, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, a 25-year old youth to fame unknown, took off in his plane The Spirit of St. Louis from Roosevelt Field, New York, on a 3,600 mile, danger fraught journey to Paris. When asked about the flight, his mother told reporters that the next day would be “either the happiest day in my whole life, or the saddest.” A successful flight meant for Lindbergh a $25,000 prize ($332,000 in 2014 dollars) offered by Raymond Orteig. Thirty-three and one-half hours later he landed at Le Bourget Aerodrome near Paris, having completed the first solo, non-stop transatlantic flight. “This time, it ‘s done!” cried the first Le Bourget workmen to reach Lindbergh’s aircraft. (The first flight across the Atlantic had been made in May of 1919 in stages over a 24 day period by the crew of the Navy-Curtiss flying boat NC-4.)

“The Conquer of the Air” stepped from The Spirit of St. Louis an international celebrity with the public focused on his every word and deed. He had become the most famous man in the world. Not long after Lindbergh’s landing there came for him a telegram from the President of the United States, Calvin Coolidge. It read:

“The American people rejoice with me at the brilliant termination of your heroic flight. The first non-stop flight of a lone aviator across the Atlantic crowns the record of American aviation…”

Lindbergh was no “Flying Fool,” as some said, although he did enjoy the thrill of barnstorming. He ranked as a first-rate, experienced aviator, who was well aware of the challenges and possibilities of the business. He had joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, graduating first in his class from advance training at Kelly Field, Texas, in March of 1925, and at the time of his flight was a captain in the Missouri National Guard. He had also become one of the first airmail pilots, flying the U.S. mail from St. Louis to Chicago and back under the most adverse conditions. When he lifted off for Paris, he had previously logged 7,189 flights and had recorded 1,790 hours of flight time. The young man conceived and carefully planned his journey through the air from New York to Paris and oversaw all aspects of its preparation. He had the knowledge and the skill, along with the determination and courage, to make it a reality.

Lindbergh was no “Flying Fool,” as some said, although he did enjoy the thrill of barnstorming. He ranked as a first-rate, experienced aviator, who was well aware of the challenges and possibilities of the business. He had joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, graduating first in his class from advance training at Kelly Field, Texas, in March of 1925, and at the time of his flight was a captain in the Missouri National Guard. He had also become one of the first airmail pilots, flying the U.S. mail from St. Louis to Chicago and back under the most adverse conditions. When he lifted off for Paris, he had previously logged 7,189 flights and had recorded 1,790 hours of flight time. The young man conceived and carefully planned his journey through the air from New York to Paris and oversaw all aspects of its preparation. He had the knowledge and the skill, along with the determination and courage, to make it a reality.

At his landing at Le Bourget, luck smiled again upon Lindbergh by putting him into the hands of the U.S. Ambassador to France, Myron T. Herrick, who took an immediate liking to the young aviator and would provide him with sound advice and guidance in the hectic days ahead. Lindbergh would later describe the fatherly Herrick as “an extraordinary man.”

Herrick had instantly recognized Lindbergh potential value in winning friends for America, so he brought him back to the embassy to place him, as he put it, under “Uncle Sam’s roof.” By doing so, Herrick was putting on Lindbergh the imprimatur of the United State Government. He proceeded to turn the young aviator—a polite, modest, plainspoken young man, assured of himself and blessed with common sense–into America’s “Winged Ambassador.” Lindbergh went on to win the hearts of the people of France, Belgium, and Great Britain. Among the royalty he met was the Princess Elizabeth, the then one-year-old daughter of the Duke and Duchess of York and now HM Queen Elizabeth II.

President Calvin Coolidge sent the cruiser U.S.S. Memphis to returned Lindbergh and his plane to the United States. By doing so, President Coolidge was bestowing on Lindbergh an honor never before accorded a private citizen. While homeward bound, the President directed that Lindbergh be promoted to the rank of colonel in the regular U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. The President also invited the aviator, along with his mother, to stay with the Coolidges at the temporary White House at 15 Dupont Circle during his stay in the nation’s capital.

On June 11, 1927, the Memphis steamed up the Potomac into the Washington Naval Yard, where it docked at the place usually reserved for the presidential yacht Mayflower. The welcoming ceremony that followed at the base of the Washington Monument was a spectacular and emotional affair attended by an estimated 250,000 individuals. The pictures and newsreels of the day reveal a crowd of happy, smiling faces. The occasion was one of the truly great moments in American history and stands as the high-water mark of the Nineteen-Twenties.

Among the smiling participants was President Calvin Coolidge, who presided over the proceedings, which were broadcast via a 50-station radio hook-up into homes across the land. One account states, “President Coolidge eulogized [Lindbergh] in one of the most feeling speeches of the statesman’s career.” He referred to Lindbergh as “our messenger of peace and goodwill,” “our ambassador without portfolio,” and said that his glorious triumph would always live in the hearts of the people of all nations because he had proven “a modest American youth, with the naturalness, the simplicity, and poise of true greatness,” and had “returned home unspoiled” after receiving a homage such as might turn the head of almost any man.

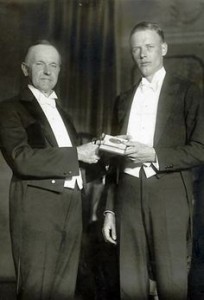

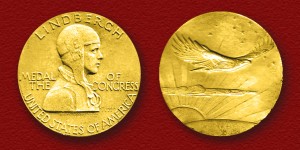

The President then honored Lindbergh by decorating him with the Distinguished Flying Cross. In the coming months, the President would be present Lindbergh with other awards, including the Gold Hubbard Medal of the National Geographic Society (November 14, 1927) for his service to the science of aviation and the Congressional Medal of Honor (March 21, 1928).

Lindbergh went on from Washington to New York City for a spectacular tickertape parade and then to St. Louis, his home from which he planned the flight, for a memorable homecoming. From July to October 1927, he toured the country over on behalf of aviation. This undertaking was sponsored by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund and took him to all 48 States during which he flew 22,350 and made 82 stops and delivered 147 speeches. It was while on this tour that he dropped from his plane a note of greeting to the folks at Plymouth Notch. Lindbergh’s national tour was followed by a triumphal “Good Will Tour” to Mexico in December and later in 1928 to Central and South America, where he again proved himself to be America’s Winged Ambassador.

It was while in Mexico that young Lindbergh would meet his future bride, Anne Morrow, the daughter of the American Ambassador Dwight Morrow, who was an old college friend and long-time supporter of Calvin Coolidge.

After the Latin America flight, Lindbergh turned over the Spirit of St. Louis to the Smithsonian Institution on April 30, 1928. It can now be seen on display in the National Air and Space Museum.

Charles A. Lindbergh went on to live a long and productive life, marked at times by personal tragedy and political controversy. He died on the island of Maui on August 26, 1974.

Those wishing further information on Charles Lindbergh can go to Amity Shlaes’ Coolidge, A. Scott Berg’s Lindbergh, or to Lindbergh’s own Pulitzer Prize-winning account of his flight, The Spirit of St. Louis.

I am reading book lindbergh by A Scott Berg . I am a retired commercial pilot and have great admiration for his beliefs and accomplishments.