From the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation Spring 2011 Newsletter:

By Bill Brooks, Former Development Director and current Executive Director of the Henry Sheldon Museum

As the 1924 presidential election approached, two leading African American Republican Party leaders, longtime associates of President Calvin Coolidge, were divided on their endorsements. William Clarence Matthews (1877 – 1928) endorsed Calvin Coolidge and William Henry Lewis (1868-1949) endorsed the Democratic Party nominee John W. Davis of West Virginia.

Both gentlemen were from the south – Lewis was born in Berkley, Virginia, the son of former slaves, and Matthews was born in Selma, Alabama. Lewis attended Amherst College from 1888-1992, while Coolidge was there from 1891-1895; they overlapped during one academic year. Lewis went on to Harvard Law School 1892-1894, where Matthews was later an undergraduate from 1901-1905. Both Lewis and Matthews were spectacular athletes. Lewis played football at both Amherst and Harvard and then coached at Harvard from 1895 to 1906, and he trained Matthews, who excelled in both football and baseball. They were loyal Republicans, the party of Lincoln, as were most African Americans of the period. [During their lifetimes they were identified as “colored” or Negro,” but I have chosen to use the modern identification of African American.]

The issue that led to their contradictory presidential endorsements centered on the party platforms, or rather their interpretations of those platforms, and the candidates’ positions on the Ku Klux Klan. Lewis concluded that the Republican Party platform was not strong enough in its criticism of the KKK and censured President Coolidge for not being more public in denouncing the Klan. He issued a fifteen page criticism of the Republican Party platform and the President on the issue of the KKK. Lewis endorsed the candidacy of John W. Davis of West Virginia based on the Davis renunciation of the KKK in a speech by Davis on August 21, 1924 at Sea Girt, New Jersey: “If any organization, no matter what it chooses to be called, whether it be KKK or any other name, raises the standard of racial and religious prejudices, or attempts to make racial origins or religious beliefs the test of fitness for public office, it does violence to the spirit of American institutions and must be condemned by all those who believe in American ideals.”

William Henry Lewis

In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt advocated Lewis’s appointment as Assistant District Attorney of Boston and later Naturalization Attorney for all New England. In October 1910, President William Howard Taft appointed Lewis as the United States Assistant Attorney General. After a prolonged fight in the U.S. Senate, Lewis’ nomination was confirmed in June 1911. With the election of Woodrow Wilson the next year, his federal patronage position ceased and he then practiced law full time in Boston.

In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt advocated Lewis’s appointment as Assistant District Attorney of Boston and later Naturalization Attorney for all New England. In October 1910, President William Howard Taft appointed Lewis as the United States Assistant Attorney General. After a prolonged fight in the U.S. Senate, Lewis’ nomination was confirmed in June 1911. With the election of Woodrow Wilson the next year, his federal patronage position ceased and he then practiced law full time in Boston.

Later, after Coolidge assumed the presidency, Lewis endeavored “to generate more Afro-American political support for the Coolidge administration throughout 1923 and 1924; Lewis was also particularly keen on recommending the political appointments of Tuskegee men of the Washington era. Demonstrating his loyalty to Coolidge and the Republican Party, Lewis anticipated receiving the administration’s high-ranking and coveted post of official political organizer within the black community during the presidential election of 1924. Frustrated with the loss of the position to another prominent black in Boston, William Matthews, Lewis defected from the Republican ranks in 1924. In returning to the party almost immediately following the election of 1924 … Lewis affected another curious volte face, but he was unable to regain his former status as a major black advisor.”2 Many concluded that his support of Davis rather than Coolidge in the 1924 election was occasioned by the President’s failure to appoint him to a federal office.

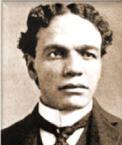

William Clarence Matthews

William Clarence Matthews, 12 years younger than Mr. Lewis had also been appointed by President Taft, but in 1912, as Special Assistant United States Attorney in Boston. Twelve years later it was he who was chosen as Head of the Colored Division of the Republican National Committee in the presidential election of 1924. His appointment followed his participation in the successful effort forcing “the G.O.P to recant their action of 1921 cutting down the Southern representation at the national convention, with the threat that the Negro race would be led en masse out of the Republican party as protest against ‘the gross injustice’ of nullifying their power in the councils of the party.” Both Lewis and Matthews were friends and longtime leaders of the Republican Party African American community. The Pittsburgh Currier3 carried an article on August 18, 1923 “Colored America Generally Ignored at Harding Funeral: Race Overlooks Rebuffs and Pays Respect in Flowers and Telegrams,” without indicating whether they attended the service in the rotunda of the Capitol or sent floral tributes noted: “William C. Matthews and William H. Lewis, distinguished citizens of Boston, are very cordially acquainted with President Coolidge, and speak very favorably of the attitude of President Coolidge on the problems of human relations.”

William Clarence Matthews, 12 years younger than Mr. Lewis had also been appointed by President Taft, but in 1912, as Special Assistant United States Attorney in Boston. Twelve years later it was he who was chosen as Head of the Colored Division of the Republican National Committee in the presidential election of 1924. His appointment followed his participation in the successful effort forcing “the G.O.P to recant their action of 1921 cutting down the Southern representation at the national convention, with the threat that the Negro race would be led en masse out of the Republican party as protest against ‘the gross injustice’ of nullifying their power in the councils of the party.” Both Lewis and Matthews were friends and longtime leaders of the Republican Party African American community. The Pittsburgh Currier3 carried an article on August 18, 1923 “Colored America Generally Ignored at Harding Funeral: Race Overlooks Rebuffs and Pays Respect in Flowers and Telegrams,” without indicating whether they attended the service in the rotunda of the Capitol or sent floral tributes noted: “William C. Matthews and William H. Lewis, distinguished citizens of Boston, are very cordially acquainted with President Coolidge, and speak very favorably of the attitude of President Coolidge on the problems of human relations.”

During the campaign their differences were quickly made public. In an interview reported by the New York Times on October 25, 1924, Matthews said: “The cooperation of the various factions of colored voters, for which I have striven from the time of my appointment, has been remarkable. It is true that the colored voter was disturbed at the beginning of the campaign by the desertion of the Republican party by such men and women as William Henry Lewis , Alice Dunbar Nelson, and others, but time has reviewed to him the following such radicals.. I am satisfied that the bulk of the colored vote will be cast for Coolidge and Dawes on election day.” He estimated that over 90% of the 5,810,000 colored votes would be cast for Coolidge.

Matthews’ criticism of the Lewis desertion was echoed by other leading African American leaders and on the editorial pages of the African-American weeklies. The black vote contributed to Coolidge’s eventual overwhelming victory over Davis and Progressive candidate Robert M. La Follette. While there was no exit polling to estimate the number of African Americans who voted for Coolidge and no known quantitative analysis of the their vote in 1924, historian John Berry noted “in the 1924 election well over 90% of northern blacks voted Republican, with most of the remaining votes going to La Follette’s Progressives, not to Democrats …”4

Following the 1924 election, William Clarence Matthews delivered a speech outlining a “Race Plank,” of seventeen demands which were part of a “comprehensive survey of conditions as they confront Negro.” Most demands dealt with appointments to federal office. Soon thereafter, Matthews was appointed to the Justice Department by President Coolidge: (1) October 1925 named a special assistant to the attorney general of the United States and posted to Lincoln, Nebraska to represent the government in certain federal prosecutions; (2) December 1925 named Assistant United States Attorney at Springfield, Illinois; (3) June 1926 reassigned to San Francisco, California in charge of water litigation for the government.

Conclusion of Careers

Matthews’ career was cut short by his death resulting from a perforated gastric ulcer in April 1928 while in Washington on government business. His funeral service, held in Boston, was attended by 1,500 mourners according to the April 21, 1928 edition of The Pittsburgh Currier. The article also reported that telegrams of condolence were sent by President Coolidge and U.S. Attorney General Sargent. Amongst the honorary pallbearers was William Henry Lewis.

Lewis lived another twenty one years practicing law in Boston until his death on January 1, 1949. Boston Mayor James Michael Curley eulogized him: “Lewis in his vast and noble labors erected his own monument.” The Chicago Defender of January 8, 1949 reported that “The passing of Mr. Lewis removes the last member of the great organization of intellectual and political power that dominated the thoughts and activities of the Afro-American people for almost half a century.” Both powerful men are buried in Cambridge Massachusetts – Matthews at the Cambridge Cemetery overlooking the Harvard Stadium, where they both played football, and Lewis at Mt. Auburn Cemetery. Men from the South who excelled as athletes and civil servants, who advanced the rights of African Americans, found rest in nearby hollowed grounds of the North.

1 Garland S. Tucker, II, The High Tide of American Conservatism, (Austin, TX, Emerald Book Co. p. 224, quoting from John W. Davis Papers, Sterling Library, Yale University).

2 Maceo Crenshaw Dailey, Jr., Calvin Coolidge’s Afro-American Connection, Contributions in Black Studies, Vol. 8, Article 7, p. 92

3 The Pittsburgh Currier, founded in 1907, and once the country’s most widely circulated black weekly newspaper with a national circulation of almost 200,000. Today it is published under the name The New Pittsburgh Courier.

4 John M. Barry, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America, (New York, N.Y., Simon & Schuster) p. 318 based on the book by Henry Lee Moon Balance of Power: The Negro Vote (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday) pp.48-50