By Robert M. Klein, M.D., Columbia University Irving Medical Center

On May 18, 1924, First Congregational Church in Washington held its regular service. But this Sunday, one important congregant was missing: President Calvin Coolidge.

The following day, The New York Times offered a reason: “For years Mr. Coolidge has been a victim of hay fever and occasionally in the Spring has suffered from an [affliction] which has the symptoms of ‘rose fever.’”[1] The newspaper account revealed that, five days earlier, a circus performance had exposed Mr. Coolidge to dust “stirred up by the performers and crowd.” The memoirs of Coolidge’s personal physician, Lieutenant Commander J.T. Boone, recount: “Whenever he would go to a circus or be around horses, he would suffer a great deal from asthmatic attack. One reason that he did not always accept an invitation by his friend, John Ringling, to go to his circus, [was] because afterwards he would be miserable, inflamed eyes, lacrimation, nasal discharge, irritated throat, [and] shortness of breath.”[2] Exposure to pollens would also provoke these symptoms.

But what was actually causing the president’s ailments? White House physicians were well aware of Coolidge’s annual allergy symptoms in the spring and summer because of prior incidents during Coolidge’s term as vice president. During Coolidge’s time serving under Harding, Major James F. Coupal, a Tufts medical graduate, was assigned to act as his physician. Under Coupal’s care, Vice President Coolidge received allergy injections in 1921.[3] Although Coolidge also appointed Charles E. Sawyer, a physician, and Boone to his staff after Harding’s death, Coupal unofficially assumed the clinical responsibilities of White House physician.

In March 1924, Coolidge expressed interest in “re-inoculation.” Boone visited Coupal to discuss the “previous inoculations that President Coolidge had had for hay fever.” Coupal informed Boone of Coolidge’s injection history and reported that the President was sensitive to June grass. Sawyer conferred with Boone about administering a “desensitizing dose for hay fever” to President Coolidge.[4] It was Boone’s recommendation that any desensitization treatment be deferred until W.T. Harrison, an Assistant Surgeon in the US Public Health Service was consulted. Harrison was conducting, “Some Experiments of the Antigenic Principles of Ragweed Pollen Extract (Ambrosia Elatior and Ambrosia Trifida).”[5] These experiments were the basis for Harrison’s later studies of ragweed pollen extracts in the treatment of ragweed pollen hypersensitivity. After gathering “a great deal of information” on the subject and discussing it with “top authorities,” Boone advised against another round of allergy injections.[6]

But the president and his entourage were ready to try a new remedy. President Coolidge elected to undergo an experimental treatment at the strong recommendation of another trusted advisor, Secretary of War John W. Weeks. Secretary Weeks pronounced that he had “cured himself of a stubborn cold” after an experimental treatment with chlorine gas and was an “enthusiastic convert to chlorine, and spread the news throughout Washington that the War Department could cure anybody’s cold.”[7]

A few days after its report on Coolidge’s missed church visit, The New York Times reported that “President Coolidge, who is still suffering with a cold symptomatic of rose fever, today took the chlorine gas treatment, with which army surgeons have been experimenting successfully for several months.”[8] Today this treatment—breathing diluted chlorine gas in a special chamber—is sometimes treated as a crucial mistake that may have contributed to Coolidge’s respiratory and cardiac troubles. These troubles may have influenced Coolidge’s decision not to run for a second elected term in 1928. Some have argued that respiratory challenges, taxing to Coolidge’s heart as they were, caused his early death at the age of just 60 in 1933. A look into the president’s chlorine gas treatment and the medical mystery of Coolidge’s death therefore warrants further inquiry.

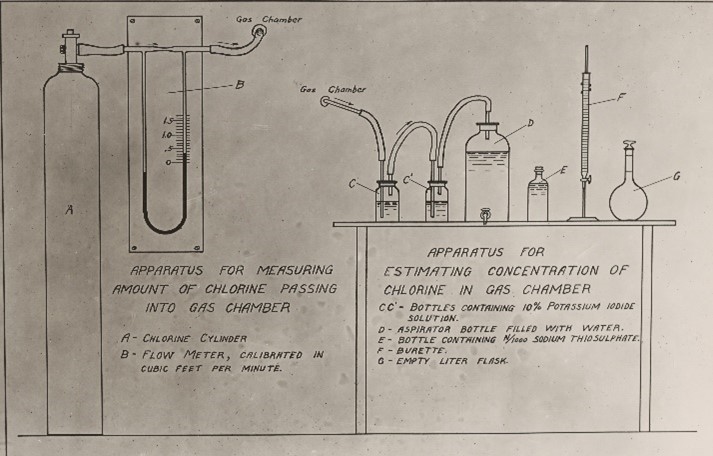

By the time Coolidge underwent this treatment, the Army doctors had been experimenting with chlorine gas for two years. Beginning in February 1924, “a gas chamber had been under constant operation. There more than two thousand persons have been treated.”[9] Two treatment stations were established, one at an Army munitions building and the other at a US Navy dispensary. Prior to these treatments, initial trials were conducted under the supervision of the Chemical Warfare Service, when 931 patients were treated with chlorine gas by Lieutenant Colonel Edward B. Vedder of the US Army Medical Corps. In order to conduct these studies, the Army constructed “an airtight chamber 13 by 13 by 10 feet, in which five or six people could sit comfortably, and through which 42,000 liters of gas-air mixture could be passed per minute, with an even distribution in the chamber.”[10]

Interest in the curative power of chlorine had first emerged in nineteenth century France. In 1819, Jean-Nicolas Gannal, a prominent French physician, observed that employees in a “bleaching establishment” were at lower risk to develop tuberculosis and proposed this as a “curative agent for phthisis.”[11] Further use of chlorine in France demonstrated that, although chlorine gas “did not cure these patients,” it “ameliorated their condition, diminished their dyspnea, promoted sleep, gave them appetite, and destroyed the fetor of their sputa.”[12] In 1824, Dr. William Wallace, a prominent Irish scientist, also published a treatise which discussed the benefits of chlorine gas.[13] Later German experiments reported that “inhalations of chlorin[e]” were effective for treatment of meningococcus and diphtheria carriers.[14]

An early commercial development of chlorine came about when synthetic indigo was extracted from chlorine, making Germany a global leader in dye production. With access to modernized facilities to process chlorine, the Germans weaponized their product and launched the first lethal gas attack at the second battle of Ypres on April 22, 1915.[15] Subjected to repeated chlorine gas attacks along the Western front, Allied soldiers relied on the Chemical Warfare Service to protect them and deploy their own weapons for defense. After World War I, many Americans advocated the abolition of the Chemical Warfare Service. The Service, however, sought evidence to justify its peacetime existence.[16] General Amos Fries, a West Point graduate and the second Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service, championed chlorine gas as “useful in peacetime, and even humane.” In an effort to win public support, Fries and a group of former chemical warfare officers organized a publicity campaign to justify the extension of the program. Fries wrote, “Our proposition is absolutely sound and I have the utmost faith that if we can get it properly before the public it cannot be beaten by any group of men.”

Among the ad hoc Army group was William Chadbourne, a former Chemical Warfare Service major who organized a group of veterans to lobby in Congress. On another front, Charles Richardson—a former Chemical Warfare Service officer employed by the International Coal Products Corporation—relied on his industry relationships to gain attention and support. Coordinating these efforts on behalf of Fries was former Lieutenant Colonel Richard Mayo-Smith.[17] After Fries helped establish a weekly paper, Chemical Warfare, its editors published articles extolling the scientific achievements of Army chemists. To address the ethical use of chlorine gas, Fries penned an article titled “The Humanity of Poison Gas” Fries, an ardent anti-communist, believed that the Chemical Warfare Service could help America avoid the threat of communism.

Fries argued, “Since less than two percent of soldiers gassed during World War I suffered death, chemical warfare could be called the most ideal and humane form of war in human history.” The Chemical Warfare Service concluded that the likely reason for “public apprehension about chemical weapons was that war gasses had no real peacetime uses.”[18] To overcome the public’s unease, Fries explored alternative commercial applications for chemical agents. Among these were Chemical Warfare Service pesticide experiments with the Department of Agriculture, studies to determine if war gas could break up crow roosts on farms, and unsuccessful attempts to create a marine paint that repelled barnacles. An independent inventor, W. O. Beckwith of Ohio, designed a chamber that would release poison gas if a safe was forced open. Although Beckwith and Fries hoped that poison gas “safe-protectors” would become popular, banks and post offices considered them a contrivance, and they were never widely used.

Seeking more ambitious plans with broader applications, Edward B. Vedder and Harold P. Sawyer launched their chlorine experiments with respiratory ailments. In 1920, Dr. Harrison Hale, a professor at the University of Arkansas, used chlorine during the influenza pandemic and concluded that students at the university who underwent chlorine inhalation treatment experienced milder influenza symptoms.[19] Noting these observations, Vedder and Sawyer reported that “no cases [of the Spanish Flu] were recorded among the operatives of the chlorin[e] plant” located at the Edgewood arsenal, where chlorine was produced at “full capacity.”[20] Based upon previous scientific publications and their own observations, Vedder and Sawyer further investigated chlorine as a therapeutic agent. They concluded that “inhalations of chlorin[e] of a concentration of 0.015 mg. per liter, for one or more hours, have a distinctly curative value in common colds, influenza, whooping cough and other respiratory diseases in which the infecting organisms are located on the surface of the mucous membranes of the respiratory passages.”[21] Of 931 patients suffering with coryza, acute laryngitis and pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, chronic rhinitis, chronic laryngitis, whooping cough, and influenza, 71.4% were “cured.”[22]

After Coolidge underwent the forty-five-minute chlorine treatment, The New York Times reported Coolidge’s remarks to the press: “He was much better… All of the depression and lack of energy which accompanies a cold, he said, had disappeared, and he expected to be able to attend all of his duties by tomorrow.”[23] The following day, Coolidge returned for a second chlorine treatment, again reporting significant relief. With an improvement in his voice, his general appearance, and energy, Coolidge was able to stroll the streets of Washington D.C.

However, as reported in The New York Times, the President quickly discovered that he was not cured. That very same week, the papers reported that “Coolidge’s bronchial cold not only has refused to yield to treatment, but grew worse.”[24] Although Coolidge insisted on speaking at the opening of the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation, he struggled to deliver his address. The New York Times noted, “several times [Coolidge] interrupted his address to clear his throat and cough, and near the end his voice became so hoarse it seemed that he might have to stop.”[25] After lunch that day, Coolidge underwent a third chlorine treatment and found “it did not loosen up the cold as he expected it would.” The New York Times, however, published a contradictory report the following day, stating that Coolidge “gave a strong testimonial to the curative properties of chlorine gas for a cold,” and that “the third dose did the work,” enabling Coolidge to work “all day without any trouble from his cold.”[26]

All of these treatments were administered over the objection of Boone. Boone disagreed with Charles Sawyer—the official White House physician—who had endorsed the treatment. Boone considered the chlorine gas treatment to be inappropriate because it was “still experimental” and “highly controversial.”[27] Prior to Coolidge’s first treatment, Boone had subjected himself to the gas treatment and “found it caused severe irritation of the nose and bronchi as well as dizziness.” He insisted on further “laboratory examinations of the president’s respiratory system” before he would permit any subsequent chlorine gas treatments. Boone shared responsibility for oversight of the President’s health, as reflected by his twice daily ritual of measuring Coolidge’s pulse. Because President Coolidge suffered with “chronic nasal and bronchial trouble,” it was not unusual for Boone to be summoned in the middle of the night. Due to the early death of Coolidge’s mother at age 39, Coolidge was constantly worried about “becoming tubercular” and frequently took “various sorts of pills upon slight provocation.”[28]

Still, the enthusiasm for chlorine gas was growing. Within a week of Coolidge’s treatment, New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Frank Monaghan announced that the first chlorine gas clinic would be installed at the “Red Cross White House,” located at 345 East 116th St.[29] Dr. Louis Harris, Director of the Bureau of Preventable Disease, stated “the chief purpose of this clinic will be to conduct a research study to prove the claims made for this method of preventing acute respiratory infections.” The city quickly opened another clinic in Chelsea to meet the high demand for Lieutenant Colonel Vedder’s experimental treatment. Vedder visited the Chelsea clinic on two occasions to verify that the treatment methods were consistent with his protocol. New York’s experimental clinics operated until August 1, 1924.[30] Although the use of chlorine gas was endorsed by Professor Marston Taylor Bogert, a prominent chemist from Columbia University, the medical profession preferred to withhold judgment until further experiments substantiated the claims made by Vedder and Sawyer.[31]

On November 29, 1924—six months after Coolidge received his treatment—the Health Department of New York City declared its chlorine gas treatments were an “unqualified failure.”[32] The report issued by Harris, the director of the Bureau of Preventable Disease, summarized the findings of 671 patients treated for rhinitis, bronchitis, laryngitis, pharyngitis, influenza, hay fever, asthma, and whooping cough. “Whereas Vedder and Sawyer reported 71.4 per cent. of their 931 patients cured,” Harris reported that “we found only 6.5 per cent. of our 506 patients cured.” Although thirteen patients with asthma claimed improvement, three cases “became decidedly worse under treatment. We would emphatically caution against the use of this gas in asthma.” Harris and his colleagues declared that the findings of Vedder and Sawyer were “unjustified and deprecate the large and unwarranted claims which have appeared in some places and which have been inspired by those interested in the sale of devices for administering this treatment.”

On January 4, 1925, General Fries of the Army Chemical Warfare Service addressed these claims against Vedder and Sawyer’s treatment protocol at a meeting of the Washington Section of the American Chemical Society.[33] Admitting that there was “no accurate record” of the results of the treatment administered in Washington, he asserted that 87% of the D.C. patients “reported themselves improved or cured.”

The therapeutic properties of chlorine gas were further examined by Dr. Harold Diehl of the University of Minnesota.[34] Diehl used a small 10 by 8 by 8.5 foot room with an apparatus to maintain a chlorine concentration between 0.015 and 0.0175 mg. per liter. He compared the results of the chlorine treatment of 425 students with colds to a group of 392 students that were given either regular medical treatment or no treatment. “Of the entire series, 51.4 per cent. of those treated with chlorin[e] and 47.9 per cent. of those given medical treatment recovered in three days; while 73.3 per cent. of those treated with chlorin[e] and 72.6 per cent. of those with medical treatment recovered within a week.” Although the percentage of patients reporting improvement within one day was slightly higher in the chlorine group, the insignificant difference between the treatment groups did not validate the findings of Vedder and Sawyer.

Despite these disappointing results, pharmaceutical manufacturer Richard, Price and Hyde of San Francisco marketed the “Chlorine Kilacold bomb,” asserting that it completely resolved 97.3% of colds, 92.9% of cases of bronchitis and 97.4% of patients with influenza.[35] “The Kilacold Chlorine bomb was a teardrop-shaped glass ampoule containing 0.35 g. of chlorine gas.” To administer this treatment, instructions directed the patient to break off the glass stem and allow the gas to permeate the room. Although the product was recommended for whooping cough, croup, and diphtheria carriers, it was not recommended for asthma. By 1925, the expanding Walgreens chain was offering the Kilacold bomb at 29 cents.

President Coolidge, for his part, did not return to the chlorine treatment. He resumed his allergy injections in July 1928. Grace Coolidge wrote to Boone, “The President begins to look rested. He had a hard time with the breathing apparatus for a while but it has almost cleared up, now. Doctor Coupal has given him two inoculations to immunize him, but they upset him, made him nervous and poisoned him, as he expresses it, so that he does not get any restful sleep.”[36] As his asthma became progressively worse, Grace Coolidge observed that Calvin used his “spray” nightly to alleviate his shortness of breath.[37] Grace’s observations mattered. Coolidge considered his wife his “guardian.”[38]

After Calvin Coolidge’s term concluded on March 4, 1929, he returned to Northampton, Massachusetts. Even though his asthma “grew steadily worse,” Coolidge did not say that his decision not to run for a second term was due to declining health. Instead, Coolidge wrote in his Autobiography that, “Although my own health has been practically perfect, yet the duties are very great and ten years would be a very heavy strain.”[39] During the year 1932, Coolidge had persistent bouts of “asthma, indigestion and bronchitis.”[40] As a result, Coolidge declined an invitation to open the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.[41] Aside from one speech in support of Herbert Hoover and a radio appearance on election eve, he was unable to “stump for Hoover” in the 1932 campaign against FDR. Coolidge confided in his friend Charles Andrews, “I’m afraid I’m all burned out.” In a belated season’s greetings message to his former Secret Service Chief, Edmund W. Starling, Coolidge wrote, “I find I am more and more worn out.”

Coolidge died on January 5, 1933. Time reported that after a brief discussion with his secretary, Coolidge “strolled to the kitchen to get a drink of water. He put a stray book neatly back into the case. He evened up pens on the desk. He idly fingered a jigsaw puzzle with his name on it. He went ‘down cellar,’ watched the furnace man shovel coal,” and went upstairs to shave. [42] Returning later, Mrs. Coolidge ascended the stairs to ask her husband to join her for lunch, only to find him lifeless “on his back in his shirtsleeves.”

What caused Coolidge’s death? Although the official cause of death recorded on the death certificate signed by Dr. Edward W. Brown was “coronary thrombosis,” The New York Times reported “it was not known that he was suffering from heart disease.”[43] Only one month prior to his death, Brown examined Coolidge and “found nothing wrong with him organically at that time.” In a 1962 recorded oral history, biographer Claude Fuess claimed that “Coolidge had had a heart attack during his presidency and knew that his days were numbered.”[44]

Considering that President Coolidge suffered from asthma and hay fever, it is surprising that White House physicians allowed him to undergo multiple experimental chlorine gas treatments. In their experiments, Vedder and Sawyer insisted on careful patient selection and stipulated that “conditions not suitable for treatment” included “tuberculosis, pneumonia, asthma and hay fever.”[45] Not only were patients with these active disorders excluded, but those with a prior history were not considered. Coolidge may not have disclosed relevant details of his medical history to the Army physicians, or Vedder and Sawyer may have discounted the severity of his asthma and allergic rhinitis in their zeal to promote the Chemical Warfare Service.

There is good reason to suspect that Calvin Coolidge may have developed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as he aged. This could have been caused by flares of poorly controlled asthma in combination with heavy cigar smoking. In retrospect, the matter of the potential adverse effects of chlorine gas can be considered, but there are no records to suggest that Coolidge received subsequent gas treatments after 1924. Beyond the toxic adverse effects on the airways and distal lung tissue, the effects of chlorine exposure also include sinus tachycardia, bradycardia extrasystoles, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, and cardiomegaly.[46][47] It is unclear if “cardiac complications after inhalation of chlorine gas result from a direct toxic effect of chlorine on cardiomyocytes or they are secondary to respiratory epithelial damage and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and hypoxia.” In either case, Coolidge was not recorded as suffering from any complications after his three brief exposures to chlorine gas. A thoughtful physician today can conclude that while the gas did not help the President, it did not significantly harm him.

Calvin Coolidge’s judgment regarding participation in the chlorine gas treatments is certainly subject to question. But it is important to recall that in the 1920s many new medications were just becoming available; in the 1940s, antibiotics were also “experimental.” And it should be noted that heterodox medical treatments were more widely accepted at the time.

Unfortunately for the Army Chemical Warfare Service, therapeutic applications of chlorine gas were never realized. Chlorine is still used today as a disinfectant in drinking water, swimming pools, ornamental ponds and aquaria, sewage and wastewater, food processing systems, pulp and paper mills, and industrial water-cooling systems. The use of any chlorine gas in armed conflict, however, is banned under the terms of the 1997 Chemical Weapons Convention, overseen by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

Coolidge’s willingness to engage in these experiments can be attributed to multiple factors, including his chronic respiratory symptoms since childhood, his positive inclination for unorthodox approaches to treatment, and his trust and support of his military advisors. The three chlorine gas treatments that Coolidge received probably did not benefit him, nor is it likely that they resulted in any long-term pulmonary or cardiac consequences. The publicity from this event did help to secure the necessary support to allow the Chemical Warfare Service to continue its mission to the present day—now under the name of the U.S. Army Chemical Corps.

Robert M. Klein, M.D. is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Columbia University Medical Center.

Correspondence should be sent to e-mail rmk5@cumc.columbia.edu

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to personally acknowledge the contributions of Julie Bartlett Nelson, Calvin Coolidge Presidential Library & Museum, Kate Phillips of the Vermont Historical Society, Jerald Podair, Professor of History and Robert S. French Professor of American Studies at Lawrence University, Leonard Klein, formerly of the Pence Law Library, American University Law School and Meredith Klein of Healogics.

References:

[1] “Coolidge’s Malady Is Called ‘Rose Fever’; He Misses Church, But Will Be Out Today,” The New York Times, May 19, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/05/19/104038031.html?pageNumber=1.

[2] Joel T. Boone, Boone Papers. Chapter on President Coolidge from the Memoirs of His Physician, Joel T. Boone (1963-1965), 1070. Manuscript. From Library of Congress, Prosperity and Thrift: The Coolidge Era and the Consumer Economy, 1921-1929 (1999), http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/amrlm.mb01 (accessed January 16, 2022).

[3] Boone, Boone Papers. Chapter on President Coolidge, 234.

[4] Ibid., 257.

[5] W.T. Harrison and Charles Armstrong, “Some Experiments on the Antigenic Principles of Ragweed Pollen Extract (Ambrosia Elatior and Ambrosia Trifida),” Public Health Reports 39, no. 22 (May 30, 1924): 1261-1266, https://www/jstor.org/stable/4577178.

[6] Boone, Boone Papers. Chapter on President Coolidge, 260.

[7] “Chlorine Gas, A Cure for Colds,” Chronicle (Adelaide), August 30, 1924, 58. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/89376439/8782835

[8] “Army’s Chlorine Gas Helps Coolidge’s Cold; He Spends 45 Minutes in Air-Tight Room,” The New York Times, May 21, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/05/21/101598141.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[9] Oliver Peck Newman, “Chlorine Gas For Colds,” American Review of Reviews 71, (1925): 76.

[10] Edward B. Vedder and Harold P. Sawyer, “Chlorin as a Therapeutic Agent in Certain Respiratory Diseases,” Journal of the American Medical Association 82, no. 10 (March 8, 1924): 765.

[11] “Chlorine Remedy for Respiratory Ills,” The Pharmaceutical Era 58, (May 31, 1924): 519.

[12] Austin O’Malley, “Use of Chlorin in Respiratory Infections in 1833,” Journal of the American Medical Association 83, no. 5 (August 2, 1924): 376.

[13] Newman, “Chlorine Gas,” 71: 77.

[14] Vedder and Sawyer, “Chlorin as a Therapeutic Agent,” 82, no. 10, 764.

[15] “Gas That Killed Men Now Used to Cure Their Colds,” The New York Times, June 1, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/06/01/101600478.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[16] Thomas Faith, “As Is Proper in Republican Form of Government: Selling Chemical Warfare to Americans in the 1920s,” Federal History 2010, accessed January 16, 2022, 28.

[17] Faith, As Is Proper” 2010, 31.

[18] Ibid., 32.

[19] Vedder and Sawyer, “Chlorin as a Therapeutic Agent,” 82, no. 10, 764.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., 766.

[22] Ibid., 765.

[23] “Army’s Chlorine Gas,” The New York Times, May 21, 1924.

[24] “President’s Cold More Troublesome,” The New York Times, May 23, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/05/23/101598754.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Coolidge’s Cold is Cured,” The New York Times, May 24, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/05/24/104699845.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[27] Milton F. Heller Jr., The Presidents’ Doctor: An Insider View of Three First Families (New York: Vantage Press, 2000), 79.

[28] Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1967), 140.

[29] “City to Open Clinic for Gas Cold Cure,” The New York Times, May 27, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/05/27/119039167.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[30] “Find Chlorine Gas No Cure for Colds,” The New York Times, November 30, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/11/30/98809579.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[31] “Gas That Killed Men Now Used to Cure Their Colds,” The New York Times, June 1, 1924, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/06/01/101600478.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[32] “Find Chlorine Gas No Cure for Colds,” The New York Times, November 30, 1924.

[33] “Gen. Fries Defends Chlorine Treatment,” The New York Times, January 6, 1925, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1925/01/06/101630834.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.

[34] Harold S. Diehl, M.D., “Value of Chlorin in the Treatment of Colds,” Journal of the American Medical Association 84, no. 22 (May 30, 1925): 1629-1632.

[35] “Bomb the first sneeze,” The Quack Doctor, https://thequackdoctor.com/index.php/bomb-the-first-sneeze-with-kilacold/.

[36] Boone, Boone Papers. Chapter on President Coolidge, 1026.

[37] Cohen, “J. Calvin Coolidge, (1872-1933) Thirtieth President of the United States,” Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 19, no. 1 (Jan-Feb 1998), 45.

[38] Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge (New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, 1929), 93.

[39] Ibid., 240.

[40] McCoy, Calvin Coolidge, 411.

[41] David Greenberg, Calvin Coolidge (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2007), 154.

[42] “National Affairs: Death of Coolidge,” Time, January 16, 1933, accessed January 16, 2022, http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/printout/0,8816,744886,00.html.

[43] “Former President Coolidge Dies,” The New York Times, January 6, 1933, accessed January 16, 2022.

[44] Robert H. Ferrell, The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge (Lawrence, Kansas: The University of Kansas Press, 1998), 204.

[45] Edward B. Vedder, “The Present Status of Chlorine Gas Therapy,” Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association 41: 209.

[46] Gary W. Hoyle and Erik R. Svendsen, “Persistent effects of chlorine inhalation on respiratory health,” Annals of the New York Academy of Science 1378, no. 1 (August 2016): 33.

[47] Ahmed Zaky, et al., “Inhaled matters of the heart,” Cardiovascular Regenerative Medicine 2, e997, 3, (December 8, 2015): accessed January 16, 2022, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4672864/pdf/nihms726327.pdf.

Thank you, Dr. Klein, for this fascinating and enlightening article. I knew that President Coolidge had received chlorine gas treatments, but I was unaware of the background behind the treatment and its effect on him. Now I know.

Your article reminded me of another President who took rat poison. After his 1955 heart attack, President Dwight Eisenhower was administered Warfarin. Warfarin had been used to kill rodents but was later found by chance by Army doctors to be an excellent anticoagulant. Ike was among the first patient to receive the drug. His successful use of it helped to popularize Warfarin, which is still widely used today.

Very well researched and an item of which I had been unaware