The decade of the 1920s is often referred to as the Republican ascendancy because of the return to conservatism in contrast to the progressivism of the early 20th century. Presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover dominated this era and tended to govern with a conservative philosophy. Nevertheless this decade was also a battleground of political philosophy between conservatives and progressives and often the role of government and the Constitution was at the center of this war of ideas. This was especially true in the United States Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court during the late 19th century — during the age of industrialization and big business — was accused by both agrarian populists and progressives by being in favor of laissez-faire economics and striking down government regulation of the economy. The most famous decision of this era, Lochner v. New York, became the symbol of a Court that stood for the protection of economic liberty, liberty of contract (the right to negotiate in the economy freely), and limiting the role of government. This philosophy is sometimes referred to as legal classicism. During the 1920s this judicial philosophy collided with the progressive view of the Constitution as a “living” document as advocated by President Woodrow Wilson and Justice Louis Brandeis.

During the 1920s this constitutional battle in the Court continued between “those struggling to maintain the older jurisprudence and those wanting the Court to promote a law reflective of newer ideas and conditions.”[1] Because of their appointments to the Supreme Court, Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover would have an impact on the future direction of the Court.

President Harding would appoint four Justices to the Supreme Court during his time in office. Harding nominated former President William Howard Taft to serve as Chief Justice and he also appointed George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, and Edward T. Sanford. All were considered conservatives in their judicial philosophies and reflected the conservatism of the era. Historian Melvin I. Urofsky notes that “the years of the Taft Court marked the high point of legal classicism…”[2]

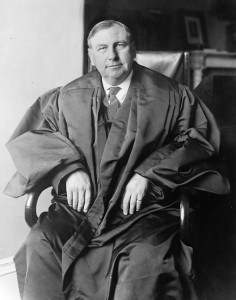

President Calvin Coolidge, upon taking office after the death of Harding, would not only continue the Harding policy program, but he also had to clean up and restore confidence to Washington, D.C. because of the scandals that emerged. Coolidge selected his former Amherst College classmate and fellow Republican from New England, Harlan Fiske Stone, to serve as Attorney General.[3] Stone had attended Columbia University Law School, “taught and practiced law for a quarter of a century, attaining the deanship at Columbia in 1910.”[4] In replacing Harry M. Daugherty as Attorney General, Stone brought integrity back to the Justice Department by helping Coolidge eliminate the corruption by some members of the Harding administration.[5]

For Coolidge, Harlan F. Stone was not just Attorney General, but also a friend who helped in the Coolidge landslide victory in the 1924 presidential election.[6] In 1925 when Justice Joseph McKenna retired from the Court, Coolidge nominated his friend Harlan F. Stone to the Court.[7] Chief Justice Taft, who often advised both Harding and Coolidge on judicial appointments, approved of Stone’s nomination to the Court and as Henry J. Abraham noted that the “Big Chief” tried to claim credit for the nomination, but “there is little doubt that the decision to send Stone to the Court was Coolidge’s alone.”[8]

Harlan F. Stone was also seen as a reliable Republican who carried the favor of not only his friend Coolidge, but also the Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, who was also a close friend. Stone brought credibility because of his handling of the Justice Department in the aftermath of the Harding administration scandals, but Abraham notes that Stone’s nomination did create some problems with some Senators such as Burton K. Wheeler, a Montana Democrat.[9] Because of this opposition Stone became the first Court nominee to actually appear and testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee. He not only had Coolidge’s continued support, but won confirmation easily in the Senate.[10]

As a new Justice on the Supreme Court, Stone was now part of the conservative Taft Court and he became increasingly uncomfortable with the conservative Justices and he started to lean toward the progressive Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis. In response to Stone’s drift toward the progressives, Melvin Urofsky wrote that “Taft complained to his brother that insofar as maintaining the proper conservative jurisprudence, ‘Brandeis is of course hopeless, as Holmes is, and as Stone is.’”[11] Urofsky states that Brandeis, Holmes, and Stone “did not agree on everything, but they did share a belief in what Brandeis had called a ‘living law,’ one attuned to changes taking place in the broader economy and society.”[12]

President Coolidge’s only nomination to the Supreme Court would become a victory for the progressives during the 1930s and into the 1940s. Coolidge himself did not agree with the progressive view of a “living” Constitution that was flexible with the times. Stone would later be joined on the Court by three new members nominated by President Herbert Hoover. Hoover nominated Charles Evans Hughes as Chief Justice, who had an impeccable career in law and public service, along with Owen J. Roberts, and Benjamin Cardozo, who was a leading progressive legal scholar.

President Calvin Coolidge defended his philosophy until his untimely death in 1933, and in the aftermath Harlan F. Stone would have a major impact on American constitutional law. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal often ran into trouble as Chief Justice Hughes and the Court’s conservative members joined together to strike down several New Deal laws. Justice Stone found himself as part of the progressive element of the heavily divided Hughes Court. Eventually President Roosevelt would elevate Harlan to serve as Chief Justice from 1941 to 1946. Harlan F. Stone’s tenure on the Court is seen as successful, especially by progressives, but as Henry J. Abraham wrote:

President Calvin Coolidge defended his philosophy until his untimely death in 1933, and in the aftermath Harlan F. Stone would have a major impact on American constitutional law. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal often ran into trouble as Chief Justice Hughes and the Court’s conservative members joined together to strike down several New Deal laws. Justice Stone found himself as part of the progressive element of the heavily divided Hughes Court. Eventually President Roosevelt would elevate Harlan to serve as Chief Justice from 1941 to 1946. Harlan F. Stone’s tenure on the Court is seen as successful, especially by progressives, but as Henry J. Abraham wrote:

Yet Coolidge was to give his country one of its most renowned Justices in the person of his Attorney General—Harlan Fiske Stone— his sole appointee to the Court. Little could the President realize that his New Hampshire-born friend Stone, the presumably safe ex-corporation lawyer with excellent Republican credentials, would within a year join the Holmes and Brandeis dissenting duo, ultimately becoming such a devoted defender of the constitutionality of New Deal legislation…[13]

Coolidge did not live long enough to witness the major constitutional battles being fought over the New Deal, but it is most certain that although he would consider Stone a friend, he would be discouraged by his embrace of the New Deal. For Calvin Coolidge, a political and philosophical conservative, Harlan Fiske Stone became his most important legacy to the progressive movement by Stone’s support of the New Deal constitutional revolution on the Supreme Court.

[1] Melvin I. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis: A Life, Pantheon Books, New York, 2009, p. 592.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., p. 576.

[4] Henry J. Abraham, Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II, fifth edition, Roman & Littlefield Publishers, New York, 2008, p. 153.

[5] Ibid., p. 152-153.

[6] Ibid., p. 153.

[7] Ibid., p. 152-153.

[8] Ibid., 152.

[9] Ibid., 153-154.

[10]Ibid., p. 154.

[11] Urofsky, p. 577-578.

[12] Ibid., p. 578.

[13] Abraham, p. 152.