GRACE COOLIDGE’S RADIO DEBUT OVER STATION NAA ON DECEMBER 4, 1922

By Jerry L. Wallace

Next year is a centennial year for President Calvin Coolidge. But this year marks a centennial for Grace Coolidge—the centennial of her broadcast in the then-young medium of commercial radio. One of the ways radio got its big start was KDKA’s election night broadcast of the Harding-Cox contest in November 1920. Among those caught up in the enthusiasm for the new medium was Grace Coolidge. While she was curious about radio’s workings, what most likely drew her to it was her love of music and baseball. Early radio stations usually provided timely baseball scores as part of their daily programming.

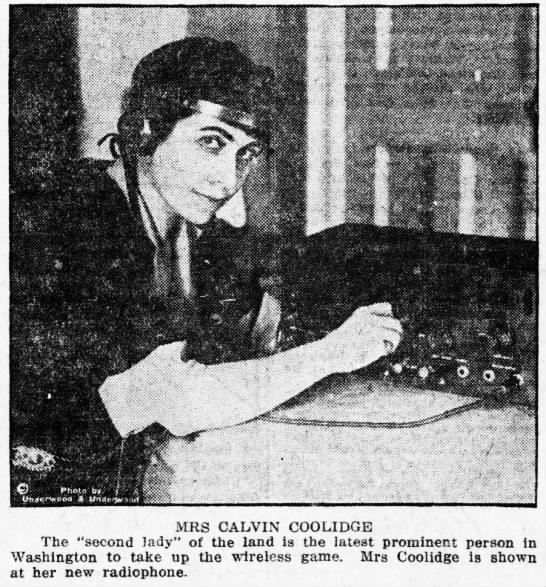

Grace Coolidge’s interest in radio became known to the newspapermen who followed her husband, Vice President Calvin Coolidge. In the spring of 1922, to boost interest in the radio, photographs began appearing in newspapers around the country of various public figures listening to their radio sets. According to Wireless Age, the theme was “National Leaders Accept Radio as Force for Good.”

The participants were all male and several were Harding cabinet members. But the radio men made an exception for the Second Lady, Grace Coolidge. The photographers, Underwood & Underwood, took an engaging picture of Mrs. Coolidge wearing earphones while working the dials on her radio receiver. This photograph, taken in the Coolidge suite at the Willard Hotel, appeared in papers around the country. Meanwhile, articles about Grace Coolidge and photos of her were appearing frequently in the press—making her a public figure in her own right.

At the time the vice president was not an especial radio enthusiast. He left the radio listening, he said, to Mrs. Coolidge. But the vice president quickly recognized the political value of broadcast radio for reaching the American electorate. In May 1922, he made his first radio speech outside of Washington at a gathering of the Presbyterian General Assembly in Des Moines, Iowa. Coolidge also made another historic broadcast during 1922, a Christmas eve greeting to the nation.

It was a fundraising drive that drew Grace Coolidge to the radio. The Women’s Union Christian Colleges for Girls in the Orient sought to raise $2,000,000 for use to support Christian colleges for women in India, China, and Japan. The fundraisers aimed to raise $2,000,000. As now, pressure was applied by a big donor with a matching challenge. The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Fund agreed to provide an additional $1,000,000 dollars if the $2 million goal was met by the end of January 1923. That would bring the total to $3,000,000.

Mission board members from several denominations worked together to organize the drive. In Washington, the fundraising effort was headed by Mrs. Wallace Radcliffe, who, as Peter Marshall noted, “was no mere person. She was rather a personage.” Among its principal members were “Mrs. Coolidge and Mrs. Hughes, and other leading women of the Cabinet, Supreme Court, and Congressional circles.”

The fundraising began in January 1922 when the first lady, Florence Harding, gave the project her blessing and sent a gift of money. Mrs. Harding wrote to the organizers:

“In this day when so many efforts are being made to bring about a better understanding between all nations our women are offered a great opportunity to help this end by furthering the establishment of women’s colleges in the Orient. I wish you therefore all success in the campaign.”

A key part of the fundraising effort did not get underway until June 5, 1922 when Dr. Ida S. Scudder, a missionary doctor and founder of the Christian Medical College and Hospital at Vellore in British India, arrived in the United States. Scudder, whose family had long been engaged in medical missionary work in India, seemed an ideal fundraiser. Given Scudder’s two decades of frontline experience in India, she could speak with authority on the need for more schools in Asia.

Seeking donations, Scudder traveled the country, going as far west as Omaha and speaking to churches, colleges, and women’s clubs. As the December deadline approached, the $2,000,000 goal had not been reached. To close the gap, Americans were asked by Scudder to give $1.00 to the cause on “Dollar Day.”

The Washington group decided it would be advantageous to have Scudder broadcast an appeal for funds, both locally and nationally. This meant two separate broadcasts in which Scudder would speak for ten minutes on the topic: “The Last Lap of the Race for the Women’s Union Christian Colleges for the Girls of the Orient.”

Mrs. Coolidge was asked to introduce Scudder on the national broadcast. Grace accepted but was probably reluctant to do so because she found women’s voices on the radio unpleasant. Indeed, when Grace heard them, she turned them off. In this, she was not unique. Some radio stations would not allow women with high-pitched voices on the air. But, in this instance, the request was only for brief remarks, and Mrs. Coolidge assented.

The first broadcast took place on December 2 over a local Washington, D.C. radio station, WIAY, owned by Woodward & Lothrop—a local department store. Scudder was introduced by Rev. William F. McDowell, Bishop of the Washington Methodist Episcopal Church, who gave a three-minute talk.

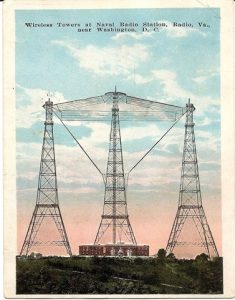

The second broadcast—on which Mrs. Coolidge made her radio debut—took place on December 4 at 6:45 p.m. This broadcast took place over the Naval Radio Station NAA, located in Arlington, Virginia on Radio Hill. NAA’S large towers loomed over the city. This powerful station had a range of around 1,500 miles, reaching into the nation’s heartland. Grace Coolidge spoke briefly in introducing Scudder. Unfortunately, we have no record of what she said.

In advance of the broadcast, some newspapers alerted their readers to Scudder’s appearance and prominently noted that Mrs. Coolidge would introduce her. Afterwards, papers across the country put out brief articles on this appeal for funds, the headline of which often read as if Mrs. Coolidge had made the appeal. Here is an example: “Mrs. Coolidge Asks For Three Millions – Wife of Vice President Radio Appeal in Behalf of Missions.” Moreover, these articles contained only a passing or no mention of Scudder’s talk which was the heart of the broadcast. One wonders how Mrs. Coolidge, as well as the vice president, reacted to this distortion of what had taken place. Pictures of Mrs. Coolidge and Scudder would also appear in the Sunday photogravure section of several papers.

All these efforts appeared to be for naught. The year ended without reaching the $2,000,000 goal. But Ellen Scripps of the Scripps newspaper chain came to the rescue by providing the needed funds, and the $3,000,000 was secured for women’s education.

There were attempts to bring Mrs. Coolidge back to the microphone, but she made no more radio appearances until Inauguration Day 1929. On that day, the Coolidges boarded the train taking them back home to Northampton. Before the train steamed out of Union Station, Grace joined Calvin in saying “Good-by, folks” to the network microphones. And those two words uttered to an invisible audience were Grace Coolidge’s second and last known radio appearance.

Jerry L. Wallace is a Coolidge historian whose interest in Calvin Coolidge and the 1920s dates back more than 65 years. He has been a member of the Coolidge Foundation since 1973 and served a term as a trustee of the Coolidge Foundation. Mr. Wallace is now a member of the Foundation’s National Advisory Board. He has written extensively on Coolidge, including in the essay Calvin Coolidge: Our First Radio President. A historian and archivist, Mr. Wallace served at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC. Now retired and living in Oxford, Kansas, Mr. Wallace spends his time researching and writing on Coolidge and local Kansas history.

Sources:

- “Mrs. Coolidge a Fan,” Radio Age (Sept. 1923), p. 19.

- Ishbel Ross, Grace Coolidge And Her Era: The Story Of A President’s Wife.

- Lillian Rogers Parks, My Thirty Years Backstairs at the White House.

- Wireless Age (June 1922), p. 24.

- Howard Q. Quint & Robert H. Ferrell, eds., The Talkative President (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1964).

- C. Bascom Slemp, The Mind of the President.

- “Coolidge Talks To Iowans Via Register Radio,” Des Moines (IA) Register, May 22, 1922, p. 12.

- Dorothy Clarke Wilson, Dr. Ida: The Story of Dr. Ida Scudder of Vellore.

- “Women’s Union To Collect Funds,” Washington Times, Dec. 2, 1922, p. 6.

- “America To Aid Women Of Asia,” Lancaster (PA) New Era, Dec. 4, 1922, p. 2.

- “Soprano Voices Barred From Radio By Station WBBM,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), Oct. 11, 1925, p. 36.

- Washington Times, Dec. 5, 1922, p. 14.

- Evening Star (Washington, DC), Dec. 2, 1922, p. 4.

- “Arlington Radio Station To Install Radiophone,” Boston Globe, Apr. 30, 1922, p. 77.

- “Broadcasting at NAA Begins Soon,” Dispatch (Moline, Ill.), Dec. 22, 1922, p. 5.

- “Radio News,” Evening Star (Washington, DC), Dec. 3, 1922, p. 32.

- “Mrs. Coolidge Ask For Three Millions,” Morning News (Wilmington, DE), Dec. 5, 1922, p. 6.

- Cincinnati Enquirer, Dec 24, 1922, p. 49.

- “Mrs. Coolidge Likes Radio, But Refuses to Broadcast,” Sacramento (CA) Bee, Mar. 9, 1929, p. 28.

- New York Times, Oct. 18, 1924, p. 3.