Recalling Calvin Coolidge: A Man of Noble Character by Jerry L. Wallace

Beginnings

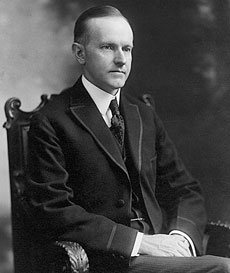

John Calvin Coolidge was born in 1872 on the Fourth of July and in the 96th year of American Independence. The child was named for his father, but the family dropped the John, calling him Calvin or Cal.

His birthplace was Plymouth Notch, a small hamlet tucked away in the Green Mountains of Vermont. His ancestors were among the earliest settlers in the area. The Notch was a place he would always hold dear and to which he would frequently return for renewal. As president, he became closely associated with it. And, after his death, Coolidge’s friends decided that the Plymouth Notch homestead and environs should be preserved as his memorial.[i]

Coolidge’s father was a man of ability and high character. Coolidge would always admire and respect him and ever sought to please him through his achievements in life. Interestingly, through his father’s line, Coolidge inherited a few drops of Indian blood, something he liked to note. As president, Coolidge would sign legislation granting all Native Americans U.S. citizenship. While not rich, his father was a man of substance for that time and place. He engaged in farming and various business pursuits, including operating the local store and serving as postmaster. His fellow citizens respected and trusted him. Over many years, he played a prominent part in community affairs, serving in local and state offices. As a result of serving on Governor Stickney’s military staff, the title of “Colonel” was bestowed upon him in 1900, and thereafter, he was addressed as such.

His mother was Victoria Josephine Moor Coolidge, a beautiful lady, we are told, bearing the name of two empresses. She and her husband John grew up together in the Notch and were married there on May 6, 1868. She was a frail individual, having, Coolidge wrote, “a touch of mysticism and poetry in her nature which made her love to gaze at the purple sunsets and watch the evening stars.”[ii]

Coolidge’s boyhood in Plymouth Notch was an ordinary one. He wrote of it, “Country life does not always have breadth, but it has depth. It is neither artificial nor superficial, but is kept close to the realities.”[iii Beginning in September of 1877, he went to school up the road from the Coolidge homestead. His grades were good but unexceptional. There was nothing to set him apart, other than, perhaps, his shyness and frailty. He performed chores faithfully; the wood box was always full. He worked on the farm, helping with haying, bringing in the grain, and husking the corn. He also hunted and fished and liked to ride. He attended dances in the room over the country store, but he himself did not take to the floor. One of his favorite times of the year was the maple sugar season. Cal, his father said, could get more sap out of a tree than anyone else.

Tragedy came early into Coolidge’s life. In March of 1885, when he was but 12 years old, death took his mother away. His father and grandmother Coolidge did their best to make up for the loss. He lamented, “The greatest grief that can come to a boy came to me. Life was never to seem the same again.”[iv] As with many nineteenth century men, he was devoted to the memory of his mother. His deep and abiding love for her is revealed in his Autobiography. He would carry with him a locket containing her portrait until he went to join her. Five years after his mother’s passing, he would suffer another heavy blow with the death of beloved sister, Abigail, or Abbie as he called her. Something of her personality comes through in her favorite quotation: “Count the day lost / Whose low descending sun / Sees from they hand / No worthy action done.”[v]

In September of 1891, Coolidge’s father would marry a neighboring woman, a school teacher, Caroline Athelia Brown. Coolidge had known Carrie, as she was called, all his life. She was a good, caring woman who treated him as if he were her own son. “For thirty years,” he wrote in his Autobiography, “she watched over me and loved me…” [vi]

Black River Academy

In February of 1886, at 13 years, Calvin Coolidge broke with the past when he entered the Black River Academy—an institution similar to a high school—at Ludlow. It was, he said, his first great adventure. “I was perfectly certain,” he later wrote, “that I was traveling out of the darkness into the light.”[vii] The academy, with a Baptist affiliation, had a student body of around 125 students and had just celebrated its 50th anniversary. Coolidge’s father, mother, and grandmother had attended the school for a few terms.

To prepare for future college work, Coolidge took the classical course, with its focus on Latin, Greek, history, and mathematics. Such course work, he would later observe, provided the ideals necessary to give direction to a person’s life. During his first term, he began his lifelong study of the Constitution of the United States. Years later he would praise that great charter, writing that “no other document devised by the hand of man ever brought so much progress and happiness to humanity.”[viii] His tuition was about $7.00 a term, and his room and board ran no more than $3.00 per week.

Coolidge graduated from the Black River Academy on the 23rd of May 1890. His class consisted of five boys and four girls. At the ceremony in Hammon Hall, he spoke on “Oratory in History,” in which he assessed the degree to which public speaking had influenced the course of world history. This presentation was Coolidge’s first noted public address.[ix] He had intended to enter Amherst that fall but following an illness, decided instead to take preparatory work during the spring term at St. Johnsbury Academy.

In August of 1891, Coolidge beheld his first president, Benjamin Harrison, when he attended with his father the dedication of the Bennington Battle Monument. “As I looked on him and realized that he personally represented the glory and dignity of the United States,” he wrote, “I wondered how it felt to bear so much responsibility and little thought I should ever know.”[x]

Amherst College

On September 17, 1891, the 19-year-old Coolidge entered Amherst College. His years there were critical to his intellectual, personal, and career development. Later in life, philosophizing on the purpose of education, he would say, “Education is to teach men not what to think but how to think.”[i] He studied under several fine professors, who, he found, were more than simply teachers but were “men of character,” whose words had an especially profound and lasting impact upon him.[ii] Notably, this was true of Charles E. Garman, who taught philosophy. Garman re-enforced in Coolidge his beliefs in the common man and in the value of work and gave him a broader outlook on life, one that would allow him to grow as a person over time. Most importantly, Coolidge learned from Garman “the law of service, under which men are not so solicitous about what they shall get as they are about what they shall give.”[iii] Coolidge would follow its dictates all his life. It would form the basis for his long career of public service.[iv]

Coolidge enjoyed the social life of the college, although, because of his shyness, he remained in the background. Yet he made acquaintances, men such as Dwight Morrow, a future financier. These men, along with other Amherst alumni, such as Frank W. Stearns, a wealthy Boston merchant, would later play a significant role in urging and cheering him on in his political career. Stearns, in particular, would become his friend and principal backer.

He joined the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity, in which he would take a lifelong interest. Recognizing his oratorical skills, at commencement time, his classmates honored him by choosing him to be Grove Orator. In this role, he was charged with making his audience laugh, and laugh they did. On the 26th day of June 1895, Calvin Coolidge graduated A.B., cum laude.

While at Amherst, Coolidge entered an essay contest on “The Principles Fought for in the American Revolution,” sponsored by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. The contest was opened to all seniors at American colleges and universities. His paper won the silver medal at Amherst and then went on to be awarded first prize—a gold medal (about 7.5 ozs)—from among all the papers submitted nationally. This was quite an academic honor for the young Coolidge. It demonstrated his scholarly abilities and writing skills, which would later reappear in his public papers. Coolidge’s pride in his essay was such that years later, he included it in The Price of Freedom (1924), a volume of his addresses and writings.

After graduation, Coolidge returned to Plymouth Notch to work on his father’s farm for the summer. Coolidge had decided upon a career in law and wished to attend law school. His father, however, thought it best that he read the law at an established law firm—an old-fashion but practical and inexpensive way of learning the law.[v] Fortune smiled on Coolidge: He secured a place in the offices of John C. Hammond and Henry P. Field, both Amherst graduates, located in Northampton, Massachusetts, a city then of about 15,000 souls. In a sense, Coolidge was returning to his ancestral home, for his ancestors had lived in Massachusetts for 150 years before migrating to Vermont.

While still in college, in thinking of his future home, Coolidge had written his father in a Garman-like fashion, “I should like to live where I can be of some use to the world and not simply where I should get a few dollars together.”[vi] His wish was granted: His new hometown and state would welcome him and lay before him numerous opportunities for public service in the years ahead.

On His Own

It was on September 23, 1895, that Coolidge began his lawyer apprenticeship. Hammond and Field, both fine attorneys, took the young man under their wing. As always with Coolidge, he applied himself fully and in time, became proficient at his new profession. Just two days before his 25th birthday in 1897, Coolidge was admitted to the Massachusetts bar. The following year, on February 1, 1898, he opened his own law office on the second floor of the Masonic block on Main Street. Inspiring confidence and trust, he built a solid reputation for himself and slowly his practice grew. Over time, he would become an attorney for the Springfield Brewery and counsel for the Nonotuck Savings Bank, the largest savings institution in Northampton. He was noted for settling his clients’ cases out of court, if possible, saving them time and money. He willingly helped all, including the poor, who came to him for assistance. His fees were so low that his colleagues in the law upbraided him for not charging more.

Marriage

By the turn of the century, Coolidge had become an established lawyer and was active in civic affairs. All that was missing from his life was a wife. This problem was remedied when he met the beautiful and charming, Grace Anna Goodhue, a teacher at the Clarke School for the Deaf. Love bloomed at first sight. His wooing of her was successful, and overcoming his future mother-in-law’s objections, they were married on the 4th of October 1905, at Grace’s parents’ home in Burlington, Vermont.

Grace was truly the love of his life. “A man,” Coolidge wrote, “who has the companionship of a lovely and gracious woman enjoys the supreme blessing that life can give. And no citizen of the United States knows the truth of this statement more than I.”[vii] He would always want Grace by his side. As a companion, with her friendly, outgoing personality, she compensated for his silent reserve. “We thought we were made for each other,” he observed. “For almost a quarter of a century she has borne with my infirmities, and I have rejoiced in her graces.”[viii] The family made their home in a rented duplex at 21 Massasoit Street.

Their first child, who they called John, arrived on September 7, 1906. He would live a long and productive life, dying in May of 2000. A second child, Calvin, Jr., came on April 13, 1908. This child, who resembled his father both in looks and in his ways, would die tragically in July of 1924 at the beginning of the presidential election campaign. His death, as only a child’s death can, took a heavy toll on Coolidge, and for a time, Melancholy marked him for her own. “When he went,” he sadly wrote, “the power and the glory of the Presidency went with him.”[ix] Less than two years later, he lost his elderly father as well.

Politics and Office Holding

Calvin Coolidge was born into politics. Indeed, his father was first elected to the Vermont legislature a month after Coolidge’s birth. As a young child, Coolidge would visit him at the Capitol at Montpelier and while there, he sat in the Governor’s chair. Later, he would attend town meetings with his father and observe how he handled himself and dealt with issues facing the community. When Coolidge became president, he wrote his father, “I am sure I came to it [i.e., the presidency] largely by your bringing up and your example.”[i] He also experienced democracy at first hand, and in doing so, he gain a lasting respect for the average citizen and the electoral process. He would later say, “There is something in every town meeting, in every election, that approaches very near to the sublime.”[ii] For Coolidge, local government and local responsibility were at the heart of the American democracy. His faith in the people was absolute. “In time of crisis,” Coolidge wrote in his Autobiography, “my belief that people can know the truth, that when it is presented to them they must accept it, has saved me from many of the counsels of expediency.”[iii]

The importance of elections was brought home to Coolidge in the Garfield-Hancock presidential campaign of 1880, when he was eight years old. He asked his father for a penny to buy a stick of horehound candy. His father replied that it was best to wait, for an election was underway and if the Democrat Hancock was successful at the polls, hard times were sure to follow. Garfield triumphed, however, and Coolidge got his candy.

In the fall of 1888, while at the Black River Academy, Coolidge experienced his first presidential campaign. It was between Cleveland and Harrison, and he joined in celebrating the latter’s victory for two nights. He was 16 at the time. In the presidential election of 1892, he joined the Amherst Republican Club and participated in torchlight parades. This time, however, his candidate failed and he learned the sorrow of political defeat. In 1893, at the request of his Plymouth neighbors, the budding politician gave his first of what would be many Fourth of July speeches. “While that flag floats,” he exclaimed, pointing to the Stars-and-Strips, “our rights shall be preserved.”[iv]

When Coolidge left Amherst, he commented to a friend, “I’m only sure of one thing—that I’m a Republican.”[v]

His Republicanism was based firmly in a belief in the party’s ideals and in the correctness of its fundamental policies on the great issues of the day, such as the protective tariff that was designed to nurture American manufacturing. Coolidge would be a consistent and an unwavering party man till the end, but never was he an extreme partisan.[vi] He had many friends among his opponents; indeed, at his death, Al Smith, the 1928 Democrat presidential candidate, would compose one of the more insightful Coolidge obituaries, entitled “A Shining Public Example.”[vii] As for parties themselves, he believed that by providing a point of responsibility, they were essential to the functioning of the American political system.

Hammond and Field encouraged Coolidge to involve himself in Northampton politics. Although reserved, he had a genuine common touch and enjoyed talking politics with average citizens, such as James Lucey, a cobbler and active Democrat, with whom Coolidge had become acquainted while in college. Lucey liked the young man, becoming his friend and advisor and helping him in local politics. There is some irony in that the Republican Coolidge’s first letter from the White House was to the Democrat Lucey. Coolidge wrote him, “…I want you to know that, if it were not for you, I should not be here…”[viii] Like a true politician, Coolidge never forgot his friends who helped him along the way.

Coolidge began his involvement in Northampton politics in the fall of 1895 when he helped Henry P. Field in his race for mayor. The following year, 1896, Coolidge participated in one of the most exciting and important presidential election in our history: the great battle between Bryan and McKinley. Coolidge, who was able to vote for the first time in this election, did his part by writing an article for a local newspaper attacking Bryan. While vacationing at Plymouth Notch that summer, he defended the gold standard in debate, which pleased his father. It was also at this time that he received his first political assignment, serving as an alternative delegate to a local party convention to nominate a state senator. He was finding his calling in life; he was becoming a politician.

Up the Political Ladder

Coolidge was once asked if he had hobby. He replied, “Holding office.”[ix] Over the years, Calvin Coolidge would run for public office 17 times (excluding primaries). This number is high because in Coolidge’s day, elections in Massachusetts were held annually. Coolidge probably put himself before the people’s judgment more than any of our other presidents.

He was a first rate politician and a consistent vote getter, especially good at attracting Irish Democrat voters, many of whom were enthusiastic for him. He managed all his early campaigns on his own, and he won each race but one, a seat on the Northampton school committee in 1905. He always ran positive campaigns focusing on the issues.

Voters came to see Coolidge as a man of character who knew his business and could be trusted to do the day’s work. Moreover, there was never a hint of scandal, personal or political, attached to his name. Having the people’s confidence served Coolidge well as a public figure when, for instance, he had to resolve the messy scandals left him by the Harding Administration after assuming the presidency. His great success as a politician was due to his listening to the people and doing what they wanted done. For example, as president, coming into office after the Great War, this would involve restoring the United States to a peacetime basis or, as Warren G. Harding so well put it, returning country to “normalcy.”[x]

His grounding in politics, legislating, and public administration was thorough. He started at the bottom of the political ladder and worked his way to the top. He held both legislative and administrative positions—excelling at both, a rare combination in a politician. In his 23 years in elective office, the following are the eight positions he held by gift of the people, along with his dates of service.

- Northampton City Councilman, 1899 (one term)

- Representative to the General Court, 1907-08 (two terms)

- Mayor of Northampton, 1910-11 (two terms)

- State Senator, 1912-15 (four terms), serving as President of the Senate, 1914-15

- Lieutenant Governor, 1916-18 (three terms)

- Governor of the Commonwealth, 1919-20 (two terms)

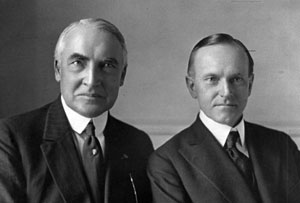

- Vice President of the United States, Mar. 4, 1921, to Aug. 2, 1923, when he was called to the presidency upon the death of President Warren Gamaliel Harding. Partial term: 2 years and 5 months.

- President of the United States, Aug. 2, 1923 to Mar. 4, 1929, elected in his own right on Nov. 4, 1924. Partial and one full term: 5 years and 7 months.

Coolidge also held other positions during these years. They included:

- Northampton City Solicitor, 1900-01. Two appointments. Chosen by the City Council. Passed over for a third appointment.

- Clerk of the Court of Hampshire County pro tempore, 1903. Appointed by the Court. Served out the term of the deceased incumbent; declined to run for election to the post.

Reflections on a Politician and Statesman

In his political thinking, Coolidge was at heart a conservative. This is seen in his focus on preserving individual liberty and freedom, his defense of property rights, his support of religion, his encouragement of tolerance by personal example in a time of intolerance, and his Burkean respect for the law and the time-honored institutions and customs of society. When it came to new legislation, he was concerned that it not only be constitutional but also met a genuine need in a practical fashion. He was never quick to legislate. He was, in fact, more concerned with stopping bad legislation than passing good. Yet he was not afraid to use the powers of government, when necessary, to address exceptional public needs, as demonstrated during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, when government agencies and the Red Cross combined efforts to meet the crisis.

Coolidge was attuned to the public mood, and he did support progressive or liberal measures during his days in Massachusetts politics. Indeed, early on, he was considered a liberal. He was sympathetic to the causes of woman and labor and worked on their behalf. And throughout his career, he was a staunch supporter of education, raising teachers’ salaries as mayor and proposing a Department of Education and Relief as president. It must be understood that Coolidge was proud of Massachusetts—then an example to the nation of an enlightened, progressive state—and what it had accomplished for the well being of its citizens through its institutions, public and private.

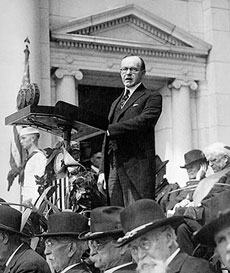

It was while governor of the Commonwealth that Coolidge faced the greatest challenge of his political career: the Boston Police Strike of 1919, one of those sad, tragic happenings that should never have been. Here he was faced with a challenge that could either make him politically or destroy his career.[i] Standing firmly for the right as he saw it, he navigated the storm successfully.

At the end of it all, he clearly and definitively expressed the issue at the heart of the crisis: “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”[ii] In these few words, he summed up the nation’s mood. The Democrat President Woodrow Wilson congratulated him on his firm stand against this “crime against civilization.”[iii] On the floor of the U.S. Senate, Senator Charles S. Thomas, a Democrat of Colorado, remarked, “It is to such men [as Coolidge] that we must look for the preservation of American institutions.”[iv] That fall the voters of the Commonwealth returned Calvin Coolidge to office in historic landslide victory. —Vox Populi, Vox Dei!

As a consequence of the police strike, Coolidge reaped praise and gained a national fame that would propel him to the top of the political ladder. At the Republican national convention in June of 1920, the delegates, tired of being bossed by the bosses, rejected the bosses’ candidate for vice president and instead, enthusiastically chose Calvin Coolidge as Warren G. Harding’s running mate.

At Harding’s sudden passing on August 2, 1923, Calvin Coolidge was called to the presidency. Asked what thought first came to mind on receiving the news of his elevation, he replied, “I thought I could swing it.”[v] He was famously sworn into office by his father, a notary public, in the parlor of the family homestead at Plymouth Notch by the light of a kerosene lamp. This simple event captured then as it still captures today the imagination of a nation.

With his belief in local and state government as the true engine of democracy, Coolidge necessarily held a narrow Jeffersonian view regarding the functions of the national government. Indeed, his views on the subject were much more in keeping with those of Grover Cleveland, the president of his youth, than with those of Theodore Roosevelt or Woodrow Wilson. As president, he respected and honored states’ rights. He often spoke of the essential, basic role of state and local governments in our political system. “What we need,” he preached, “is not more Federal Government but better local government.”[vi] Frankly, few of his contemporaries paid him much heed, for they had learned to love, even in those pre-New Deal days, the dollars following into their communities from Washington for such popular projects as highway construction.[vii]

As president, Coolidge made himself into the nation’s chief administrator, de-emphasizing his role as a political leader, like Dwight Eisenhower would later do. His primary concern was on reducing the deficit, cutting taxes, maintaining tariff stability, and making the government run efficiently and effectively In these tasks, he excelled. Particularly notable was Coolidge’s skillful use of the newly created Bureau of the Budget in bringing order and direction to the budgeting process and thereby achieving the savings and efficiencies he sought.

On his watch, the national debt was reduced from $22.3 billion to $16.9 billion and tax rates were slashed significantly with most Americans eventually paying no Federal taxes at all. The economy boomed with industrial production increasing 70%, real earnings for wage earners growing 22%, and unemployment averaging 3.3%. Truly, Calvin Coolidge was the right man, at the place, at the right time. It should be noted that the passage of the Revenue Act of 1926, which embodied his tax policies, was the culmination of his presidency.

To build public support for his program of “constructive economy,” as he referred to it, he cleverly made pioneering use of the new medium of radio, reporting semi-annually to the public on the budget and tax matters.[viii] The radio permitted him to speak directly to the American people over the heads of politicians and newspaper editors. It helped him to block or lessen raids on the Treasury, such as those attempted by Congress in connection with Mississippi River improvements. To improve his effectiveness over the air, he brought in an expert to work with him on his radio presence. Through his extensive use of airwaves—he made over 50 major radio addresses—Coolidge became America’s first radio president.

Coolidge, of course, did not neglect the print media, it being a great source of free publicity. As president, he went out of his way to accommodate the needs of the White House press corps. For instance, he provided them with stories on slow news days and, most notably, he became the first president to hold regular, twice-weekly press conferences. He thus got along well with most newsmen, and in turn, he received generally favorable coverage in the pages of nation’s newspapers.

He also willingly satisfied the demands of camera and newsreel men, who had only recently gained access to the White House. All he asked of them was not to take his picture while he was savoring one of his favorite cigars. It is worth noting that during the 1924 campaign, he became the first president to appear in a talking newsreel. Lee de Forest produced the film in which Coolidge read excerpts from his speech accepting the Republican presidential nomination.[ix]

Coolidge was no isolationist.[x] He understood early on the new heightened status of the United States among the nations of the world. Speaking at Tremont Temple on November 2, 1918, only a few days before the Armistice, Governor Coolidge said this: “We have taken a new place among the nations. The Revolution made us a nation; the Spanish[-American] War made us a world power; the present war has given us recognition as a world power. We shall not again be considered provincial. Whether we desired it or not this position has come to us with its duties and its responsibilities.”[xi]

On the international front, the Coolidge administration supported the Dawes plan for German reparations and established accommodative payment schedules for the Allied war debt to the United States. This, along with American private loans and governmental support, gradually led the major nations of the world to restore the international gold standards, thereby spurring world trade. The administration also secured the ratification of the Kellogg-Briand Treaty outlawing war. It failed, however, because of the opposition of isolationists Senators, to secure U.S. membership on the World Court, although a revived attempt at joining it was underway at the end of the Coolidge presidency. Also, its efforts to build upon the success of the Washington Conference on the Limitation of Armaments, 1921-22, were unproductive. Notably, the administration through the good work of Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow did succeed in restoring our strained relations with Mexico at a time when some were pressing for intervention in that unhappy country. As President, Coolidge did venture outside of the United States on one occasion. This was in January of 1928, when he journeyed to Havana, Cuba, to speak to the Sixth International Conference of American States.

Coolidge’s interest in military affairs dated from 1899 when, as a city councilman, he proposed to secure an armory for Northampton. It was revived again during the Great War at the time he was serving in state government. Indeed, his first act as governor was to approve funding for a welcoming celebration for the men of Yankee Division. As president, Coolidge sought to maintain a modest military force one sufficient to meet peacetime needs. His guiding principles were, as he described them, “preparation, limitation, and renunciation.”[xii] This policy, it is worth recalling, was well suited for a time when anti-war sentiment was strong.

Not all was peaceful within the military itself: Controversy raged around Colonel William “Billy” Mitchell, a proponent of what were then advanced but controversial ideas about military aviation. Lacking restraint, Mitchell attacked the military establishment for being hidebound, going so far as to accuse its leaders of an “almost treasonable administration of the nation’s defense.”[xiii] This could not go on. Eventually, at the direct order of President Coolidge, Mitchell was court-martialed for insubordination. Having been found guilty, he resigned from the Army.

Coolidge was the last president never to have flown in an airplane, yet he well understood the value of aviation and supported its development. The greatest public moment of Coolidge presidency, as well as the high water mark of the 1920s, was the welcoming home ceremony at Washington for Charles Augustus Lindbergh on June 11, 1927. It took place following the Lone Eagle’s solo flight in Spirit of St. Louis from New York to Paris in which the young, brave pilot had triumphed over Death. Thanks to radio, Americans in the cities and towns and on the farm were able to participate in this wonderful, national celebration.

With the backing of the Coolidge Administration, Lindbergh, who the President raised to rank of colonel, went on to tour the nation to build public support for aviation. Later, as America’s winged-ambassador, he made a good-will tour of Latin America, being greeted along the way by large enthusiastic crowds. Lindbergh and Coolidge developed a lasting relationship.

Military training was encouraged. Coolidge’s son John was attending a Citizens Military Training Camp when his father became president. It was Coolidge’s thinking that the national debt was the weakest link in the nation’s defense, because it reduced the funds available to meet military needs in a crisis. Thus, his debt reduction program was fundamental to strengthening the nation’s military footing. He understood, moreover, that the great strength of the country rested ultimately not on its implements of war, but on its people, its agriculture and industrial resources, and its wealth. This led him to focus primarily on issues relating to the mobilization of manpower and industry. In this matter, he called for advice upon Bernard M. Baruch, who had headed the War Industries Board during the Great War. To address the problems of war profiteering and war fortunes that had so angered the public, he urged the drafting not just men but also wealth and resources in the event of a future war. Sacrifice would be required of all and no war profits would be allowed.

Coolidge did not forget the veterans and their families. As governor and president, he supported programs for veterans, especially those aimed at the disabled. The one notable exception was his opposition to the World War soldiers’ bonus bill, which was finally passed over his veto in 1924. Besides threatening the country’s finances at a critical point, he believed this bill, with its money handouts, would diminish the value of the veterans’ service to their nation. “No person,” he firmly noted, “was ever honored for what he received. Honor has been the reward for what he gave.”[xiv]

As president, he and Mrs. Coolidge held receptions on the White House lawn at which they welcomed and entertained wounded veterans from area hospitals. Coolidge famously summed up his feelings for veterans in these words, “The nation that forgets its defenders will itself be forgotten.”[xv] He was also an enthusiastic supporter of the American Legion, which he viewed as a unifying, patriotic force in American life, speaking before its national convention as vice president in 1921 and as president in 1925. One of the highlights of his presidency was his dedication of the World War I Liberty Memorial in Kansas City on Armistice Day 1926, an event that was broadcast nationally.

The Coolidge presidency, 1923-29, was a most successful one. That was certainly the overwhelming judgment of most of Coolidge’s contemporaries. The President was fortunate to preside over what was probably the most exciting, vital, and creative decade of the twentith Century. It was a decade of youth. It was a decade when modern America came alive. Not all was perfect by any means: There were pockets of unemployment; some farmers were hard pressed; and most disturbing, intolerance manifested itself in the form of the Ku Klux Klan. Yet, it was overall an era marked by peace and unprecedented prosperity. Most Americans had never had it so good. And some would later argue that it was the last time the American people were truly free.

As president, Coolidge achieved his principal objectives of debt reduction and tax reform, along with downsizing the government to reflect post-war needs. When he left office, he did so knowing that he had been a good and faithful servant; his stewardship well done.

Although the Coolidge administration was focused on catching up with existing legislation rather than enacting new, there was notable legislation passed and signed. Four measures that stand out are these:

- the Revenue Act of 1926, which embodied the Coolidge-Mellon tax policies that were at the heart of the administration’s program of fiscal reform;

- the Air Commerce Act of 1926, which regulated civil aviation and made possible the development of this new industry;

- the Public Buildings Act of 1926, which authorized the start of construction on the magnificent Federal Triangle complex of buildings in the nation’s capital; and

- the Federal Radio Act of 1927, which put in place a regulatory framework for the new media under which it would thrive.

Attached to this essay is a listing of important legislation of the Coolidge era.

Coolidge also successfully blocked many of those initiatives he opposed, most notably the McNary-Haugen farm relief bill, which he rejected mainly on constitutional grounds and twice vetoed. In the case of the Mississippi River Flood Control Act of 1928, the President worked with Congress to turn a flawed and fiscally irresponsible measure into a responsible bill that he could sign. He was not, however, always successful, as in his attempt to remove the Japanese exclusion provision from the Immigration Act of 1924, a bipartisan measure having overwhelming public and Congressional support. And it must be recorded that there were also several instances of Coolidge supported initiatives that went nowhere in the Congress; these included legislation addressing railroad consolidation, government reorganization, and an anti-lynching measure.

In all, Coolidge vetoed 20 bills and pocket vetoed another 30. Only four of his regular vetoes were overridden, but among them was the popular and costly Soldiers’ Bonus Bill. Here, Coolidge put himself in opposition to the Congress and their constituents, especially veterans—and he lost. But the people seemed to admire him for having the courage of his convictions, and to lessen criticism, he acted promptly to implement the legislation.

Coolidge enjoyed a widespread popularity and could easily have won re-election in 1928. Instead, he chose not to run again. Personal Factors played a role in his decision, as well as the realization that his work was done and that the public was ready for a new man with a new approach. He remarked to a Cabinet member, “I know how to save money. All my training has been in that direction. The country is in a sound financial condition. Perhaps the time has come when we ought to spend money. I do not feel that I am qualified to do that.”[xvi] Moreover, as he wisely observed, “It is pretty good idea to get out when they still want you.”[xvii]

Retirement and Death

On March 4, 1929, Calvin Coolidge departed Washington to the plaudits of the public for a job well done. When a reporter asked him what he considered his most important accomplishment, he replied simply, “minding my own business.”[xviii] He returned to Northampton, there to live out the time remaining to him. He took up the pen, writing his Autobiography, contributing to periodicals, and doing a syndicated newspaper column, “Calvin Coolidge Says.” He became a director of the New York Life Insurance Co. and at President Hoover’s request, served on the National Transportation Committee, both transportation and insurance being subjects that had long interested him. He and Mrs. Coolidge travelled about the county: He dined with Huey Long, Governor of Louisiana; he dedicated an Arizona dam named in his honor; and even visited Hollywood and stayed at Hearst’s San Simeon estate. He withdrew from active politics, limiting himself to a few political addresses on behalf of the beleaguered Hoover administration. His health was not good, and worries over the ever-deepening Depression definitely preyed upon him. Death, in the form of heart attack, came for him on the 5th of January 1933, at the age of 60 years. He never lived to see the coming of the New Deal. He rests today among his ancestors in the cemetery at Plymouth Notch. [xix]

[i] Channing H. Cox, a friend of Coolidge and former Governor of Massachusetts, was one of the first to call for this in his eulogy on Coolidge, delivered to the General Court on March 1, 1933, about two months after Coolidge’s death. “At such a shrine,” Cox said, “love for American traditions will be kindled anew and faith in American institutions will be deepened”; see Memorial Address By Channing H. Cox In connection with the Memorial Services Held by the General Court in Joint Session In Memory of Calvin Coolidge, March 1, 1933, The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Senate No. 360, pp. 26-27.

[ii] Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge (New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corp., 1929), p. 13.

[v] Hendrik Booraem, The Provincial: Calvin Coolidge and His World, 1885-1895 (Lewisburg: Bucknell university Press, 1994), p. 97.

[vi] Coolidge, Autobiography, p. 52.

[ix] A copy of this speech is available on the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation website. An article, “Calvin Coolidge’s First Speech,” by Dr. Robert H. Ferrell , which includes a copy of the speech, is found in The Real Calvin Coolidge #14, pp. 28-32.

[x] Coolidge, Autobiography, p. 49.

[i] Calvin Coolidge, Have Faith in Massachusetts: A Collection of Speeches and Messages (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919), p. 155.

[ii] Coolidge, Autobiography, p. 70.

[iv] When Coolidge came into the presidency in 1923, his net worth was estimated at a modest $10,000, which would be the equivalent today of $125,000 adjusted for inflation; see They Told Barron, ed. by Arthur Pound and Samuel T. Moore (New York: Harper, 1930), p. 351. He was 48 years old at the time, with a wife and two children, who had to educate. He owned no home and had no retirement plan.

[v] If you wish, you can still read the law in Vermont.

[vi] Claude M. Fuess, The Man From Vermont: Calvin Coolidge (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1940), p. 67.

[vii] Peter Hannaford, The Quotable Calvin Coolidge: Sensible Words for a New Century (Bennington, VT: Images from the Past, 2001), p. 51.

[viii] Coolidge, Autobiography, p. 93.

[i] Your Son, Calvin Coolidge, ed. by Edward Connery Lathem (Montpelier, VT: Vermont Historical Society, 1968), p. 211.

[ii] Calvin Coolidge, Foundations of the Republic (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926), p. 67.

[iii] Coolidge, Autobiography, p. 67.

[iv] Booraem, The Provincial, p. 147.

[vi] In November of 1905, Coolidge suffered his only electoral defeat at the hand of Democrat John J. Kennedy in a race for school board. Three years later, when Kennedy ran for re-election, Coolidge supported him. When asked why, he replied that Kennedy had a good record—also his wife and her friends thought highly of Kennedy. See Robert Sobel, Coolidge: An American Enigma (Washington: Regnery Publishing, 1998), p. 59.

[vii] Smith’s obit is reprinted in Edward Connery Lathem’s Meet Calvin Coolidge: the Man Behind the Myth (Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Green Press, 1960), pp. 219-220.

[viii] Fuess, Coolidge., p. 315.

[ix] New York Times, Jan. 6, 1933.

[x] Speaking to the Home Market Club in Boston in May of 1920, Harding rhapsodized, “America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums but normalcy; not revolution but restoration…not surgery but serenity.” See Robert K. Murray, The Harding Era: Warren G. Harding And His Administration (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1969), p. 70.

[i] In his Autobiography, Coolidge wondered if the strike might not have been “a design to injure me politically”; see Coolidge, Autobiography, p. 141. No doubt but that his opposition would have liked to damage his reputation with labor, and the strike did offer such an opportunity.

[ii] Calvin Coolidge, Have Faith In Massachusetts: A Collection of Speeches and Messages (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919), p. 223.

[iii] New York Times, Sept. 12, 1919.

[iv] Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President (New York: Macmillan Co., 1967), p. 93.

[vi] Calvin Coolidge, Foundations of the Republic (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1926), p. 228.

[vii] In one of his last newspaper columns, dated June 20, 1931, Coolidge bemoaned, “The centralization of power in Washington, which nearly all members of Congress deplore in their speech and then support by their votes, steadily increases…Individual self-reliance is disappearing and local self-government is being undermined”; see Calvin Coolidge Says, ed. by Edward Connery Lathem (Plymouth, VT: Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation, 1972).

[viii] President Coolidge made these reports in January and June of each year before the Government Organization of Businessmen, a group of high level bureaucrats set up to assist in the implementation of the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921. He made a total of 10 such reports between June 1924 and January 1929, all but one of which was broadcast nationally.

[ix] De Forest made three talking newsreel films featuring the three 1924 presidential candidates, Coolidge, Davis, and La Follette. They could be shown in only especially equipped theatres.

[x] One of Coolidge more critical biographers, William Allen White, made a point of this; see his A Puritan In Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge (New York: Macmillan Co., 1938), p. 143. It must be remembered that initially Coolidge was a supporter of the League of Nation; note his welcome home address to Wilson upon the latter’s arrival in Boston from Paris on February 24, 1919.

[xi] Coolidge, Have Faith In Massachusetts, p. 153.

[xiii] Billy Mitchell, retrieved 4-12-2012 from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Mitchell_(general)

[xiv] Coolidge, Have Faith in Massachusetts, p. 173.

[xv] Hannaford, The Quotable Calvin Coolidge, p. 160.

[xvi] Lawrence E. Wikander, “Calvin Coolidge” in, The Northampton Book (Northampton: Tercentenary History Commission, 1954), p. 302.

[xvii] Robert Sobel, Coolidge: An American Enigma (Washington: Regnery Publishing, 1998), p. 373.

[xviii] Howard H. Quint and Robert H. Ferrell, The Talkative President: The Off-The-Record Press Conferences of Calvin Coolidge (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1964), p. 19. This statement was made at his last press conference on March 1, 1929, three days before he left office. The full quote is: “Perhaps one of the most important accomplishments of my administration has been minding my own business.”

[xix] It was Coolidge’s official biographer, Claude M. Fuess who described the former president as “a man of noble character”; see his Coolidge, p. 299….Coolidge had this to say about character: “Character is what a person is; it represents the aggregate of distinctive mental and moral qualities belonging to an individual or race. Good character means a mental and moral fiber of a high order, one which may be woven into the fabric of the community and State, going to make a great nation…”; see Coolidge, Foundations of the Republic, p. 393.

Jerry L. Wallace is a Coolidge scholar, whose interest in Calvin Coolidge and the 1920s dates back over half a century. He has been a member of the Coolidge Foundation since 1972 and has served as a Trustee and is now a member of the National Advisory Board. He has written extensively on Coolidge, with his latest publication being Calvin Coolidge: Our First Radio President. By profession, he is an historian and archivist, formerly with the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC. Now retired and living in Oxford, KS, he spends his time researching and writing on Coolidge and local Kansas history.

Please click here for Photo Permissions Policy Statement