By The Honorable French Hill

Tax reform isn’t easy, but it is possible. Even dramatic tax reform.

Today, when many doubt that proposition, it’s useful to look back at another tax reform, the tax cut campaign of the 1920s. That tax reform took effort and years. Its heroes include names we have almost forgotten, such as Congressman Nicholas Longworth of Ohio, or Andrew Mellon of the Treasury. The campaign endured many setbacks. But the reform become law, and it did succeed, making strong prosperity possible. Today, with so many doubters, the how and why of that century-ago endeavor, and its heroes, make for a timely story.

America emerged from World War One lurching under a debt so enormous it was greater than the entire pre-war federal budget. Both during the war and after, Presidential Wilson and Congress raised income tax rates in the name of collecting desperately needed revenue. The tax’s structure was “progressive”—the more you earned, the higher the rate you paid on the last dollar you earned. But the yields from raising rates—at the end of the war the top marginal rate on the income tax stood at 77%—over and over proved disappointing.[1] And business and citizens alike struggled under such confiscatory taxation. The income tax was then young—less than a decade old, but politicians, especially Democrats, were already beginning to find political utility in a progressive rate structure; high rates punished the rich. At the Wilson Treasury, nonetheless, officials began to discuss whether another approach might work better. Perhaps lower rates would promote more activity. Among those officials was Russell Leffingwell, who began to talk about what was becoming known as “scientific” taxation. Leffingwell had a protégé named S. Parker Gilbert, who was also interested in developing a more productive tax regime.

It’s important to note that Leffingwell and Gilbert’s scientific tax reform plan had the support of two former Democratic Treasury Secretaries: Carter Glass and David Houston.[2] To give credit where credit is due, President Woodrow Wilson also recognized the problem, telling the nation, “There is a point at which in peace times high rates of income and profits taxes discourage energy, remove the incentive to new enterprise, encourage extravagant expenditures and produce industrial stagnation with consequent unemployment and other attendant evils.”[3]

But the Wilson Administration and Congress dropped the top rate only a few percentage points, to 73%. And by 1920, the Republicans were claiming and broadening the tax issue. Warren Harding of Ohio and Calvin Coolidge campaigned under the slogan of “normalcy,” including a return to “the prewar climate of low taxes, balanced budgets, manageable national debt, limited government, and a functioning international economy backed by the gold standard.”[4] Tax simplification was part of the Grand Old Party platform. So was lowering rates generally. Dramatically reducing the top tax rates was key to normalcy. And normalcy won, with Republicans taking strong majorities in both houses.

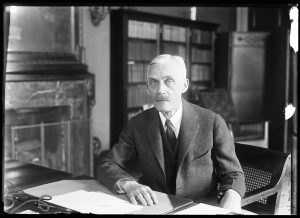

The new president placed an experienced star in the post of Treasury Secretary, one of America’s wealthiest and most adroit financiers, Andrew Mellon (pictured left). Mellon knew writing tax reform was a big job and picked his team for talent—not political affiliation. He named the talented young Parker Gilbert to the powerful post of Undersecretary of the Treasury.[5] Among those who appreciated Mellon’s sharp economic focus was Vice President Coolidge, who himself believed in the primacy of government restraint. The pair met in Harding cabinet meetings; both silent men, observers joked that Mellon and Coolidge “conversed in pauses.”

Under Gilbert’s careful stewardship, the Treasury crafted its baby: a reform of the tax code that aimed to take the top rate down from the 70% range to, say, 25% or 30%. In his years of overseeing railroads, Mellon had observed that when it came to freight rates, railroads could only charge “what the traffic will bear.” Raise the cost of shipping too high, and the customers would turn elsewhere to move their goods. Perhaps the same principle might hold for taxation. Mellon therefore sought lower rates across the board, an effective flattening of the progressive rate structure. As Mellon would tell Congress, “to reduce the surtax rates to a maximum of 25 per cent and graduating the reductions through all the brackets” might mean an “apparent loss of…revenue.” But the loss of revenue “would not be permanent, for the reduced rates would ultimately be productive of more revenue than higher rates, due to the increase in taxable transactions.”[6]

Just after Harding’s inauguration, Mellon launched the reform. His Treasury worked with Republicans in Congress, including a veteran lawmaker and member of the Ways and Means Committee, Nick Longworth of Ohio. (Longworth was married to the daughter of his party’s progressive star, Theodore Roosevelt. But Longworth himself was more conservative.) In the early 1920s the economy was suffering a sharp downturn. More and more, the tax cutters faced opposition, including in their own party, where a progressive farm bloc was building. Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, a progressive Republican, opposed rate cuts that might benefit the rich. Making matters worse, a sharp downturn in the economy was unifying opponents of tax cuts of any kind. The resulting November 1921 tax bill was a compromise that made only modest changes. The law dropped the top rate to 58% but dramatically lowered the threshold at which a taxpayer was subject to that rate.

In 1922, the prospects for reform darkened. Longworth, a conservative Republican in Congress, was watching his party founder. In the midterm elections that month, the Republicans retained their Senate majority but were weakened by a decline of seven seats.[7] Perhaps worse yet, a Republican of a different philosophy to Longworth, the progressive Senator La Follette of Wisconsin, won his state by a landslide, increasing the clout of a new Midwestern, populist farm bloc. That year the Republicans also managed to maintain control in the House of Representatives, but their margin there was also narrowing. Longworth ruefully described the margin as a “paper rather than an actual majority.”[8]

The momentum was in the wrong direction. Longworth had hoped to win the post of House Majority Leader. But La Follette-inspired insurgent Republicans, many younger than Longworth, were bypassing him and looking to select a leader among younger progressives. Distracted by other issues, and corruption in his own administration, President Harding had little time to devote to pushing further on tax reform.

Nonetheless, the Republican tax cutters did not give up. Treasury Undersecretary Parker Gilbert advised that the right move for the moment was to press for action in the House where Longworth, a point man, would not have to contend with the increasingly mighty La Follette. Gilbert also saw that a tax reform that didn’t thrill Congress might please the voting citizen more. The economy was on its way to recovery. In the 1924 presidential election Republicans would have a chance to campaign on tax cuts and remind legislators of the cuts’ importance to voters.

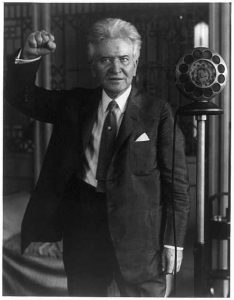

Meanwhile, in 1923, fate conspired to improve the prospects for Republicans and their tax reform. That August, President Harding passed away suddenly. It was a tragic turn but one that gave the nation a leader more temperamentally and philosophically inclined to lead a tax war: Calvin Coolidge. One of the first to recognize the opportunity was Congressman Longworth (pictured right). Longworth and his sister Clara were in Paris when Harding died, and they went to the service in Harding’s memory at the American church there. But they also reacted quickly to the prospect of the Coolidge presidency. At the time Nick remarked that “Calvin Coolidge was not popular with the ‘boys of the party’ but that he himself felt sure that the Vice President would make good if he got strong support.”[9] Nick’s sister Clara says in her memoir that Nick’s telegram of congratulations from Paris was one the “first of such messages” Coolidge received.

The new president indeed fulfilled Longworth’s hopes. Among Coolidge’s first moves was to reject Mellon’s polite resignation—indeed, in footage of one of the first press photo sessions, Coolidge can be seen patting the seat next to him to signal that Mellon should sit there. Parker Gilbert was leaving Treasury, but his successor, Gerard Winston, would work on the tax project.

At noon on a freezing Thursday in December 1923 before a Joint Session of Congress, Coolidge wholeheartedly endorsed what was now becoming known as the Mellon Plan. Coolidge argued that “high taxes reach everywhere and burden everybody. They bear most heavily upon the poor. They diminish industry and commerce. They make agriculture unprofitable. They increase the rates on transportation. They are a charge on every necessary of life.”[10] His address was met by “loud cheers from the gallery” and was well regarded by the press. [11] As it was one of the first such speeches carried on live radio, over one million Americans heard Coolidge’s speech.[12] The tax campaign was relaunched.

To win in the House, the tax plan needed a leader there. After a brutal contest, Longworth was elected House Majority Leader by voice vote on December 1st.[13] Longworth continued his work on the Ways and Means Committee and was now perfectly positioned to guide further tax reform through. (pictured left: Andrew Mellon and Parker Gilbert)

But smooth sailing was not yet to be. A threat came from one of Longworth’s old buddies on the Ways and Means Committee, the senior Democratic Congressman John “Cactus Jack” Garner of Texas. Garner proposed an alternative to the Mellon Plan. Garner structured his alternative to reduce rates, especially for lower earners. But he retained the high progressive tax rate structure, with a top rate close to 50%.

Garner was not to be underestimated, and no one knew that better than his close friend Nick Longworth. Both lawyers, both former members of their state legislatures, Nick and Cactus Jack were both sworn into their first congressional term in 1903. Both had long service on the House Foreign Affairs and Ways and Means Committees, and they had developed a long, personal friendship. That friendship was illustrated by a daily bond exercised each afternoon at 5 o’clock in Room H-128 of the Capitol known as the “Board of Education” (pictured below, right) where they would share a cocktail and school newer members. Much later, in 1926, following tax reform’s success, Longworth would tell an Ohio audience that Garner was “the ablest and most astute leader of the Democracy in either House…”[14] And, after becoming Speaker of the House in 1925, Longworth picked up Jack for work at his home for a ride to the Hill in the Speaker’s chauffeured car, “our carriage.”[15]

From February until June 1924, the two friends and legislative masters duked it out. In the end, the Democrats teamed with the La Follette insurgents to beat the Mellon Plan, producing a tax bill that lowered rates, somewhat, but also lowered thresholds for top earners and contained nasty provisions which publicized the amounts of tax top earners paid. The compromise was so awful that Coolidge must have grit his teeth.

Meanwhile, Republicans were simultaneously taking their philosophy to the public. All spring, tax reformers including Majority Leader Longworth, Undersecretary Winston, Chambers of Commerce, and Bankers League promoters were dispatched across the nation, preaching the benefits to the economy and individual families of the Mellon Plan. Tax Clubs were established to discuss tax philosophy. But the ultimate public relations tool was the release of a book in April entitled Taxation: The People’s Business. Mellon himself was listed as author on the cover. The publisher “sent countless free copies of the book directly to schools, colleges, public libraries, and chambers of commerce.”[16]

Meanwhile, Republicans were simultaneously taking their philosophy to the public. All spring, tax reformers including Majority Leader Longworth, Undersecretary Winston, Chambers of Commerce, and Bankers League promoters were dispatched across the nation, preaching the benefits to the economy and individual families of the Mellon Plan. Tax Clubs were established to discuss tax philosophy. But the ultimate public relations tool was the release of a book in April entitled Taxation: The People’s Business. Mellon himself was listed as author on the cover. The publisher “sent countless free copies of the book directly to schools, colleges, public libraries, and chambers of commerce.”[16]

In the 1924 Republican platform, true to Gilbert’s advice to Secretary Mellon, Candidate Coolidge and the GOP committed to “progressive tax reduction through tax reforms.” The Democrats and progressives fought back. The Democratic platform denounced “the Mellon tax plan as a device to relieve multi-millionaires at the expense of other taxpayers.”[17] Senator La Follette and the insurgent Republicans formed a new third party, the Progressives. In the fall the senator ran as their candidate for president. He argued for an excess profits tax, for an increase in the inheritance tax—and against the Mellon Plan.

Longworth rejected the Progressives vehemently, even arguing that his late father-in-law, Theodore Roosevelt “had no sympathy with the LaFolletteism of his day,” and that “he would be today, a sincere and aggressive supporter of Calvin Coolidge.” Longworth called the senator from Wisconsin the “most dangerous, radical of the present day.”[18]

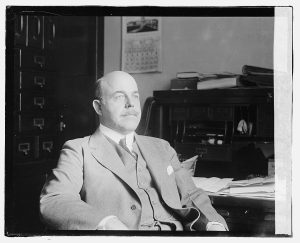

In the end, that “dangerous radical” (pictured left) didn’t do much damage. Coolidge won the 1924 election in a landslide, winning 54% of the vote in the three-way race, 35 states, and an Electoral College victory of 382-136-13.[19]

To a post-election audience in New York, a jubilant Longworth summarized the shift: “I look forward to the next Congress and confidently believe that it will be one of the most efficient legislative bodies in history. We will have a clear working majority in both branches.” For Longworth, there was also a personal victory: he became Speaker of the House. To those rebels who had betrayed the Coolidge Grand Old Party, Longworth made it clear that there would be consequences: “The House will be composed of 247 Republicans as against the 188 Democrats and five third-party members. Of the 247 Republicans 14 or 15 openly supported the Third party candidate and opposed the election of the Republican candidate. Some of them even went so far as to leave their states and campaign against Republican candidates for Congress and in favor of Democratic candidates. These men can not and ought not to be classed as Republicans in the next Congress. They left the Republican Party deliberately and did everything possible towards its undoing. Their leaders admit that from the first they carried the fight to the Republican ticket in the campaign.”[20]

Just short of a year after Mellon’s publishing of his book urging reform and the initiation of the tax clubs around the country, the Ways and Means committee started with a bang. Speaker Longworth saw to it that Ways and Means Committee Chairman William Green introduced the Administration’s proposed revenue reform measure as “the first bill on the first day of the first session of the Sixty-ninth Congress.”[21] This time rates would be much lower. Longworth also froze out from participation in further tax reform the Republicans who had not supported Coolidge and Longworth in earlier rounds.

One figure now in the penalty box was Congressman James Frear, a rebel Republican from Wisconsin. Frear thenceforward attended committee hearings “only as a listener.”[22]

With the overwhelming Republican majority, very little argument could be made against the measure by Democrats. Following the November election, in addition to local tax clubs, representatives of or governors from 32 states made trips to the Capitol to testify. The frustrated Congressman Frear’s view was that these ill-informed governors and the tax clubbers were simply “propagandists” that were organized congressional district by congressional district and “generally composed of newspaper men, bankers, and small political wire pullers.”[23]

In the end, even Longworth’s most ardent opponent in the previous Congress, his great friend “Cactus Jack” Garner of Texas, held his fire and kept his members in line with the majority. Thus, opposition was limited to only a handful. The end result was the Revenue Act of 1926, which produced a victory for Mellon. The new law set the maximum marginal tax rate on income at 25%, at a threshold of $100,000. The estate tax also went down dramatically. But even in this round, some concessions were granted to ensure the bill’s passage: the law included much broader exemptions for individuals in the lowest income brackets, taking “about a third of the 7,300,000 income taxpayers of 1925” off the tax rolls completely.[24]

At just before ten in the morning on February 26, 1926, Congressional leaders—including Democratic Ranking Member on Ways and Means Garner, Finance Committee Chair Senator Reed Smoot, Ranking Member Herbert Simmons, House Majority Leader John Tilson, Ways and Means Chairman William Green, and Secretary Mellon—gathered with President Coolidge in his office to sign the Revenue Act of 1926. Those in the photograph imply a very bipartisan conclusion to three years of legislative battle. The saber-tooth tiger coalition in opposition to the Mellon Plan led by La Follette and Garner two years before were now purring house cats jockeying for position in a White House signing ceremony. More than a dozen reporters documented the ceremony, and Senator Simmons nearly burned Senator Smoot with his cigar in his eagerness for a bipartisan handshake. At 10:22 AM, it was done.[25]

A few lessons stand out here. One is that good plans matter. Another is that perseverance matters; it took six years for an idea to become statute. Yet another lesson is that strong leaders matter—had Coolidge waffled, or simply held silent on tax, the final, decisive piece of legislation, the 1926 Act, would never have become law. Longworth’s devotion to the cause likewise matters. But there’s a final takeaway for all of us: what’s achieved once can be achieved again, even in a period when progressivism is gaining supporters. The 1920s’ successful scientific tax reform effort was subsequently replicated by President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and by President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, as both pursued economic growth.[26]

_______

Since 2015, J. French Hill represents the Second District of Arkansas in the U.S. House of Representatives. He is a former banker, Treasury Deputy Assistant Secretary, and economic policy adviser in the George H.W. Bush White House.

[1] https://taxfoundation.org/historical-income-tax-rates-brackets/

[2] Mellon, Andrew. Taxation: The People’s Business (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1924), 11.

[3] Ibid., 129.

[4] Cannadine, David, Mellon: An American Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 278.

[5] Ibid., 286.

[6] “Mellon Asks More Revenue Revision,” Washington Post Dec. 8, 1921, 2.

[7] Cannadine, 281.

[8] Longworth, Nicholas. “Speech before the Ohio Society of New York at the Waldorf-Astoria, January 10, 1925,” Box 2, Nicholas Longworth Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 5.

[9] De Chambrun, Clara Longworth. The Making of Nicholas Longworth, (Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1933), 272.

[10] Coolidge, Calvin. “Text of President Coolidge’s Address to Congress on the Affairs of the Nation,” New York Times, December 7, 1923, 4.

[11] Murnane, M. Susan. “Selling Scientific Taxation: The Treasury Department’s Campaign for Tax Reform in the

1920’s” Law and Social Inquiry Vol. 29, No. 4 (Autumn, 2004) Wiley on behalf of the American Bar Association, 833.

[12] The Evening Star, December 6, 1923, 1.

[13] The New York Times, December 2, 1923, 1.

[14] Longworth, Nicholas. Undated speech draft from 1926. Box 2, Nicholas Longworth Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 2.

[15] De Chambrun, 283.

[16] Murnane, 840.

[17] Ibid., 841.

[18] Longworth, Nicholas. Undated hand drafted speech manuscript from 1924. Box 2, Nicholas Longworth Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 2-3.

[19] The 1924 Campaign would be “Fighting Bob” La Follette’s last stand. He died of a heart attack June 18, 1925.

[20] Longworth, “Waldorf-Astoria”, 8.

[21] Blakey, Roy G. The Revenue Act of 1926. American Economic Review 16 (3): 405.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid., 406.

[24] Ibid., 421. Blakey estimates that “about a third” of the 7.3 million taxpayers in 1925 were “exempted entirely.”

[25] The Evening Star, February 26, 1926, 1-2.

[26] For a thorough analysis of the Kennedy and Reagan tax cuts, please see JFK and the Reagan Revolution by Lawrence Kudlow and Brian Domitrovic, Portfolio Penguin New York 2016.