By John Hendrickson

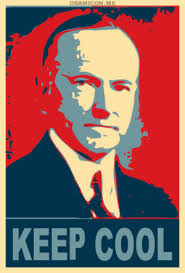

Calvin Coolidge is most often remembered for his dry wit, silence, and conservative economic and foreign policies, but he is not often remembered as a friend of labor. Coolidge himself is a living incarnation of the Protestant work ethic, which viewed labor as honorable. As Coolidge stated:

I cannot think of anything that represents the American people as a whole so adequately as honest work. We perform different tasks, but the spirit is the same. We are proud of work and ashamed of idleness. With us there is no task which is menial, no service which is degrading. All work is ennobling and all workers are ennobled.[1]

Coolidge acknowledged the importance of Labor Day when he stated that “this high tribute is paid in recognition of the worth and dignity of the men and women who toil.”[2] In addition he argued that he could not “think of any American man or woman preeminent in the history of the nation who did not reach their place through toil.”[3] Coolidge’s family upbringing built into him the understanding of hard work, thrift, and the dignity of work. He also built the value of work into his own family as demonstrated by his son Calvin Coolidge, Jr., who worked in the tobacco fields while his father was president. When other boys were astonished to see the son of a president working in the tobacco fields, one of the boys remarked to Calvin Jr., that “‘if the president was my father, I wouldn’t be working here,’” and Calvin Jr., replied “‘if your father were my father, you would.’”[4]

Even before Coolidge assumed the presidency in the aftermath of death of President Warren G. Harding, the late economic historian Robert Sobel wrote that “probably no Governor in the nation had more experience with strikes than had Coolidge in 1919, and he was considered pro-labor.”[5] As Governor of Massachusetts Coolidge won national recognition for his handling of the Boston Police Strike, when he intervened and famously stated that “there is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, anytime.”[6]

When Harding and Coolidge won the presidential election of 1920, the administration faced a tremendous crisis in labor with the depression of 1920-1921. This depression was severe as business and industry suffered and unemployment “reached 11.7 percent, some months within that year witnessed even higher unemployment — possible as much as 15 percent.”[7] Although the depression of 1920-1921 was severe, it was cut short because of the economic policies initiated by the Harding administration. These policies consisted of tax reductions, spending reductions, paying down the national debt, and tariff reform.

As President, Calvin Coolidge would continue these policies, which created a period of economic expansion and prosperity. The “Roaring Twenties” or “Coolidge Prosperity” created a period of economic expansion during the decade. “The seven years from the autumn of 1922 to the autumn of 1929 were arguably the brightest period in the economic history of the United States,” wrote economists Richard Vedder and Lowell Gallaway.[8]

The Coolidge Prosperity was not just benefiting business leaders, but common laborers as well. Robert H. Ferrell, a historian and Coolidge biographer, wrote:

One reason that workers did not enroll in unions was that they were doing much better in the 1920s. Real wages for industrial workers were 8 percent above the base year (1914= 100) in 1921, 13 percent above in 1922, and 19 percent above in 1923. For the next two years, the figure remained at this level and then increased, reaching 32 percent in 1928. The workweek declined from 47.4 hours in 1920 to 44.2 in 1929. This meant a five-and-a-half-day week…All the while unemployment was a low 3.7 percent between 1923 and 1929. This compared with 6.1 between 1911 and 1917, a fairly prosperous time for workers.[9]

Garland S. Tucker, III, in The High Tide of American Conservatism: Davis, Coolidge, and the 1924 Election, wrote that “economic facts indicate that prosperity was indeed more widespread — and more widely distributed — than at any time in American history up to this point.”[10] “Millions of Americans for the first time acquired a home, a car, and labor-saving appliances — many of the middle-class advantages that had hitherto been beyond their reach,” wrote Tucker.[11] As a result of the Coolidge Prosperity “millions of Americans entered the middle class and attained a measure of economic security they had not known before.”[12]

Coolidge’s political and moral philosophy, along with his patriotism, formed his conservative worldview. He understood that having a successful economy and decent wages depended on following fiscal prudence. It also meant following a spirit of Americanism as he stated:

We do not need to import any foreign economic ideas or any foreign government. We had better stick to the American brand of government, the American brand of equality, and the American brand of wages. America had better stay American.[13]

Coolidge, just as with past Republican administrations notably those of McKinley and Harding, argued that American wages were far better than those of Europe’s and that American wages should be protected. In his Labor Day address Coolidge argued that three policies helped in protecting the rise in American wages. These included “restrictive immigration,” a “tariff for protection,” and “economy of expenditure.”[14] Coolidge argued that “these are some of the policies which I believe we should support, in order that our country may not fail in the character of the men and women which it produces.”[15] Coolidge understood that if business was supported and encouraged by sound public policies it would “provide profitable employment.” Coolidge also argued that he did “not want to see any of the people cringing suppliants for the favor of the Government, when they should be masters of their own destiny.”[16]

Coolidge proclaimed that “one of the outstanding features of the present day is that American wage earners are living better than at any other time in our history.”[17] During the 1924 presidential campaign one of the Coolidge-Dawes campaign slogans was the “Full-Dinner Pail,” which symbolized the prosperity of the Coolidge policies. Coolidge valued American labor and the spirit of work and his policies led to job creation and economic expansion. Coolidge was truly a pro-labor President.

[1] Calvin Coolidge, “Address delivered to a group of Labor Leaders, who called on the White House, September 1, 1924,” in Foundations of the Republic, University Press of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawaii, 2004, p. 75.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robert Sobel, Coolidge: An American Enigma, Regnery Publishing, Washington, D.C., 1998, p. 239.

[5] Ibid., p. 130.

[6] Ibid., p. 144.

[7] Richard Vedder and Lowell Gallaway, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America, Holmes & Meier, New York, 1993, p. 61.

[8] Ibid., p. 68.

[9] Robert H. Ferrell, The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 1998, p. 73.

[10] Garland S. Tucker, III., The High Tide of American Conservatism: Davis, Coolidge, and the 1924 Election, Emerald Book Company, Austin, Texas, 2010, p. 37.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., p. 253.

[13] Coolidge, p. 81.

[14] Ibid., pp. 83-84.

[15] Ibid., p. 85.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., pp. 77-78.