By Jerry L. Wallace

An excerpt from Mr. Wallace’s full article, accessible in the Coolidge Virtual Library: Essays, Papers & Addresses.

This March 4th marked the 100th anniversary of Calvin Coolidge’s inauguration as Vice President of the United States. He, as Warren G. Harding’s running mate, had been elected in a landslide victory for the pair on November 2, 1920. The American people, after years of war and postwar social, economic, and political turmoil, turned to the Harding-Coolidge team with their appealing promise of “a return to normalcy.”[ii] Now, as Coolidge assumed his new national duties, he commenced a journey down a pathway that would lead him in two years and five months to the Presidency of the United States, becoming, as it was said back then, “the most powerful man in world.”

What follows is a description of principal events and happenings as they unfolded.[iii]

At about 10:00 o’clock, six cars drew up in front of the New Willard Hotel, where the Coolidges and Hardings were staying. Four cars reserved for official dignitaries, the other two, for members of the Secret Services and reporters. This little procession of motor vehicles formed the entire parade of the Harding inauguration, along with four troops of the Third U.S. Cavalry from Fort Meyers, under the command of Col. George S. Patton. With sabers drawn, the troops would ride in columns alongside the automobiles.

The members of the inaugural party—the Hardings, the Coolidges, the Marshalls, and members of the Joint Congressional Inaugural Committee—were picked up. The motorcade then proceeded at 10:20 for a short trip to the White House, where, in the Blue Room, they were greeted by President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilsons. This affair lasted about 30 minutes. Then, putting aside the old-fashion carriage, the party motored up to the Capitol building with their crack cavalry escort. Before leaving the White House, Wilson’s doctor had given him a strong drink of whiskey to brace him for the demands of the day.

Arriving at the Capitol at 11:15, President Wilson, a man broken in health, went to the President’s Room to sign nearly 30 bills—his last act as President—passed in the closing hours of the Sixty-sixth Congress. The original plan had called for Wilson to attend the swearing-in of Calvin Coolidge in the Senate Chamber and then depart, but Wilson concluded that all this would be too much of a strain for him. He called for the Vice President-elect and expressed his regrets to him in person at not being able to attend.

In the Senate that day, the first order of business was the induction into office of its new presiding officer, Calvin Coolidge, bearing the title, “President of the Senate.”[iv] These proceedings commenced at 11:45, when Vice President Marshall rapped the United States Senate to order. But there was a delay as Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and Oscar W. Underwood (D-AL) went to the President’s Room to ascertain if President Wilson had any further messages to communicate to the Senate before its final adjournment. He had none.

The swearing-in ceremony was taking place in the impressive Senate Chamber before a distinguished crowd, including President-elect Harding, members of the House and Senate, Supreme Court Justices, and envoys from foreign lands, along with other high-ranking government officials and military officers.

Witnessing the ceremony from the “Vice President’s pew” were Mrs. Coolidge, wearing a red hat, with her two sons and Col. John C. Coolidge, Calvin’s father. Mrs. Harding, accompanied by Dr. George T. Harding, Warren’s father, along with 15 other family members, was also present. She wore a blue hat and a chinchilla fur.

The Sergeant-at-Arms of the Senate, David S. Barry, appeared in the central doorway of the Chamber. Vice President Marshall bang his gavel. Barry announced to the assembly: “The members of the Committee on Arrangements and the Vice President-elect of the United States.” Coolidge, who had been waiting in the Vice President’s Room, then entered the Chamber, being escorted by Senator Knox and his colleagues on the Joint Inaugural Committee. The audience stood and applauded as Coolidge ascended the rostrum.

Vice President Marshall shook his hand. Those looking down from the galleries noted that Coolidge’s hair was a somewhat brilliant red. Coolidge’s entry was followed by that of President-elect Harding. It was at this point that the audience realized that President Wilson would not be attending, which was a disappointment to many. Senator Knox and former Speaker Cannon sat on either side of the President-elect.

At 12:21 o’clock, Calvin Coolidge, a son of Vermont, after a long and successful political career in the Bay State, raised his right hand with his left on the Bible and was sworn-in as Vice President of the United States by Vice President Thomas R. Marshall. Now, only one more rung remain on Coolidge’s political ladder of advancement.

Unlike for the President, no oath for the Vice President is provided in our Constitution. The oath used by Coolidge dated from 1884 and is still in use today.

“I, Calvin Coolidge, do solemnly swear that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God.”[v]

Marshall, a well-liked figure in the Congress, noted for his humor, then delivered his valedictory address. In it, he expressed his deep faith in the American form of government and offered a warning against hasty reforms, sentiments with which Coolidge, no doubt, fully concurred. He then proclaimed the Sixty-sixth Congress adjourned sine die and handed the gavel of authority to his successor. As he did so, the audience rose and there was great applause to mark this peaceful transfer of power.

Vice President Coolidge’s first act was to call to order a Special Session of the Sixty-seventh Congress (March 4 – 15, 1921). Next, he called upon the chaplain, J. J. Muir, for prayer. Then followed Coolidge’s inaugural address.

In his brief remarks, the new Vice President was direct and businesslike. He had, it was reported, a Yankee twang and modest presence and was clearly heard throughout the chamber.[vi] Coolidge spoke admiringly of the U.S. Senate, declaring it to be a citadel of liberty and noting that its records for wisdom had never been surpassed by any legislative body. The speech, while not memorable, was appropriate for the occasion and was well received. When he finished, President-elect Harding rose, turned out to face the rostrum, and joined in the handclapping. Throughout these proceedings, he had sat informally in a big armchair with his knees crossed.

Vice President Coolidge then administered the oath of office to the newly elected Senators. After which, he and his new Congressional colleagues proceeded to the inaugural stand on the east portico.

Chief Justice Edward Douglass White administer the oath to Warren Gamaliel Harding as the 29th President of the United States. The time was 1:18, exactly eight years to the minute from the time Woodrow Wilson took his first oath in 1913. After kissing the historic Washington Bible, Harding turned to Senator Knox and whispered, “Was it done all right?”[vii]

After his swearing-in, President Harding returned to the Senate Chamber, and there presented to the Senators the names of his nominees for his Cabinet. And, in an unprecedent move, the Senate, with Coolidge presiding, confirmed them all without further ado. It is said that the process took about 20 minutes—fast service for the U.S. Senate.

At 2:30, President Harding left the Capitol for his new home, The White House. His first presidential order was to open the White House gates to the public. The gates swung open at 4:55 and the crowds rushed in and remained until late at night. The White House itself would soon be open to visitors with passes. The grounds and building had been closed to the public since early February of 1917, when the U.S. had broken off diplomatic relations with the German Empire.[viii]

The New Era had dawn, and with it, the XXth Century that many of us would come to know.

Afterwards:

No doubt but that March 4, 1921, was certainly a day that Calvin Coolidge would long remember. For it marked the beginning for Calvin and Grace of eight momentous years in our nation’s capital. These were years that would see him both rise to the nation’s highest office upon Warren Harding’s death, as well as suffer the tragic loss of his beloved son, Calvin, Jr.

Some historians look on Coolidge’s years as Vice President as being quite unimpressive. And this does appear to be true if you chose to focus solely on his role as presiding officer of the U.S. Senate. According to one historian, Coolidge carried out his constitutional duties in “a singularly undistinguished …and [mostly] uncontroversial manner.” Poor Coolidge, alas, was never even given the opportunity to break a tie vote. In short, he “was almost a nonentity in the world’s greatest deliberative body.”[ix]

What some historians have overlooked is this: During this period of two years and five months, Providence gave Calvin Coolidge, a New England provincial, who had visited Washington only briefly before his inauguration and had no trusted, close friends there, an opportunity to well prepare himself for the time when he would suddenly be called to the Presidency in the dark of night. Coolidge himself later realized this and wrote of it at some length in his Autobiography.

And when that day of days did come on August 2, 1923, the new President of the United States could rightly think to himself: I can swing it.[x] And indeed, he, Calvin Coolidge, would be the right man at the right place at the right time.

Jerry L. Wallace is a Coolidge scholar, whose interest in Calvin Coolidge and the 1920s dates back over sixty-five years. He has been a member of the Coolidge Presidential Foundation since 1972. He has served the Foundation as a Trustee and is now a member of its National Advisory Board.

ENDNOTES

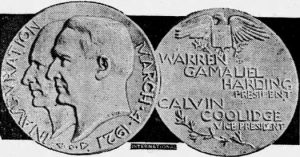

[i] This is a picture of plaster cast models of the obverse and reverse of the proposed, but never realized, Harding-Coolidge 1921 inaugural medal. The picture received wide distribution in newspapers prior to Inauguration Day. The Washington Citizens’ Inaugural Committee had a medal committee charged with producing and selling an inaugural medal. Such medals had been issued since 1901, the first being the William McKinley medal. The 1921 Inaugural Committee chose Elmer Eugene Hannan (he would later change his name to Eugene Elmer Hannan), a Washington artist, to sculpt the medal. Hannan, who was well trained and had a number of artistic works to his credit, was the son of a successful Washington businessman. He had been deaf since early childhood. One can wonder if Grace Coolidge, a teacher of the deaf, might have played a role in Hannan’s selection. This is certainly an interesting possibility, but no documentation has yet been found to support it. Because of the close-down of the 1921 Committee at Harding’s request, Hannah’s medal was never struck, only this picture of the plaster casts remains. As was customary, the committee planned to present gold medals to President Harding and Vice President Coolidge, with silver medals going to certain members of the Inaugural Committee. Bronze medals were to be sold to the public, becoming a good source of revenue for the Inaugural Committee. It should be noted that after the 1921 inauguration, arrangements were made privately for another Harding-Coolidge inaugural medal. This unofficial medal was designed by Darrell Crain and struck by R. Harris & Company. Only a few medals were struck, and today, they are quite rare and expensive. See Richard B. Dusterberg, The Official Inaugural Medals of the Presidents of the United States (Cincinnati, OH: Medallion Press, 1971), pp. 47-48.

[ii] By “normalcy,” Harding did not mean a return to the pre-war world of 1913, a world that, as most realized, was gone forever, but, rather, to a “peacetime basis.” The latter term was used by Coolidge during the campaign, and it appeared frequently in Republican campaign literature. It should also be noted that Harding did not coin the word “normalcy,” as it is sometimes suggested. The earliest record of the use of “normalcy” comes from an 1855 dictionary, published ten years before Harding’s birth. For details, see https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/did-warren-harding-coin-normalcy

[iii] Your author relied on two articles for providing him with accurate and detailed information on the March 4th inauguration of both Mr. Harding and Mr. Coolidge. They are “Scene Centers About Retirement of Wilson; Ceremonies Are Plain,” an Associated Press (AP) account found in many newspapers; and “Harding For World Court…,” New York Times, March 5, 1921, p. 1. The AP article offer a good chronology of events of the day, while the Times article provides a good deal of interesting background information. There were, of course, many other published articles dealing with various aspects of the inaugural story that were also drawn upon.

[iv] It is worth noting that Calvin Coolidge had also served in Massachusetts as President of the State Senate, January 1914 to January 1915, but his powers in Boston were much broader and more significant than those in Washington.

[v] See Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies website: https://www.inaugural.senate.gov/vice-presidents-swearing-in-ceremony/

[vi] Joe Mitchell Chapple, Life and Times of Warren G. Harding: Our After-War President (Boston: Chapple Publishing Co., 1924), p. 164.

[vii] Chapple, Warren Harding, p. 164.

[viii] On Election night, November 2nd, Florence Harding declared that one of the first acts of the Harding Administration would be to “take the policeman away from the White House gates.” See Great Falls (MT) Tribune, Mar. 5, 1921, p. 1.

[ix] Donald R. McCoy, Calvin Coolidge: The Quiet President (New York: Macmillan Co., 1967), p. 134 and 135.

[x] Claude M. Fuess, The Man From Vermont: Calvin Coolidge (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1940), p. 311.